Chronic Bronchitis with Homoeopathic management | HDS

Introduction :

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) as a disease state characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. COPD includes emphysema, an anatomically defined condition characterized by destruction and enlargement of the lung alveoli; chronic bronchitis, a clinically defined condition with chronic cough and phlegm; and small airways disease, a condition in which small bronchioles are narrowed. COPD is present only if chronic airflow obstruction occurs; chronic bronchitis without chronic airflow obstruction is not included within COPD.

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death and affects >16 million persons in the United States. COPD is also a disease of increasing public health importance around the world. GOLD estimates suggest that COPD will rise from the sixth to the third most common cause of death worldwide by 2020.

DEFINITION :

COPD :

- Fixed airflow obstruction

- Minimal or no reversibility with bronchodilators

- Minimal variability in day-to-day symptoms

- Slowly progressive and irreversible deterioration in lung function, leading to progressively worsening symptoms.

Chronic bronchitis is characterised by cough with or without expectoration for at least 3 months of the year for 2 consecutive years.

Emphysema is defined as distension of the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles with destruction of alveolar septa.

Chronic bronchitis and emphysema frequently coexist. Chronic bronchitis, over a period of time, often gets complicated by emphysema. Most of the times it is difficult to separate one from the other.

AETIOLOGY :

95% of cases are smoking-related, typically >20 pack years. COPD occurs in 10-20% of smokers, indicating that there is probable genetic susceptibility. COPD is increasing in frequency worldwide, particularly in some developing countries, due to high levels of smoking. It can also be caused by environmental and occupational factors such as dusts, chemicals, and air pollution.

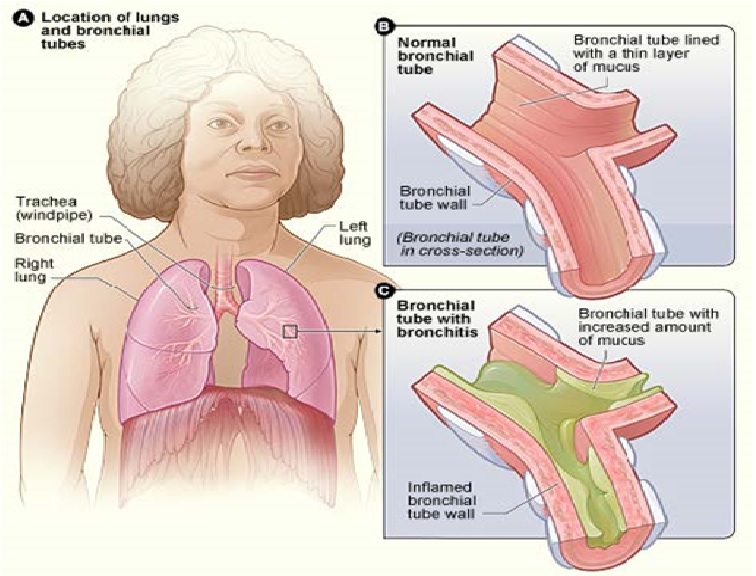

PATHOLOGY :

The pathological basis of hypersecretion of mucus is an increase in the volume of the submucosal glands, and an increase in the number and a change in the distribution of goblet cells in the surface epithelium. Submucosal glands are confined to the bronchi, decrease in number and in size in the smaller, more peripheral bronchi, and are not present in the bronchioles.

In healthy subjects who have never smoked, goblet cells are predominantly seen in the proximal airways, and decrease in number in more distal airways, being normally absent in terminal or respiratory bronchioles. By contrast, in smokers, goblet cells not only increase in number, but extend more peripherally.

The use of bronchoscopy to obtain airway cells by bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial tissue samples by biopsy has added new insights into the role of inflammation in COPD. Bronchial biopsy studies confirm those of resected lung material, which show bronchial wall inflammation in this condition. As in asthma, bronchial biopsies in patients with chronic bronchitis reveal that activated T lymphocytes are prominent in the proximal airway walls. However, in contrast to asthma, macrophages are also a prominent feature and the CD8 suppresser T-lymphocyte subset, rather than the CD4 subset, predominates.

Bronchial biopsies from limited studies in patients during exacerbations of chronic bronchitis show increased numbers of eosinophils in the bronchial walls, although their numbers are small compared with exacerbations of asthma and, by contrast to those in asthma, these cells do not appear to have degranulated.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, or more recently studies of spontaneously produced or induced sputum, have shown increased intraluminal airspace inflammation in patients with chronic bronchitis, with or without airways obstruction, and predominantly neutrophils and macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage studies. There is also evidence that airspace inflammation in patients with chronic bronchitis persists following smoking cessation if the production of sputum persists.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY :

Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are most often present together. Both result in airways narrowing but can exist without evidence of obstruction. However, by the time a patient starts getting dyspnoea as a result of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, airways obstruction is invariably present.

In chronic bronchitis and emphysema, the work of breathing is increased because of altered pressure-airflow relationship. The residual volume (RV) and functional residual capacity (FRC) are higher than normal. Total lung capacity is increased and vital capacity is decreased. Ventilation – perfusion inequality is always present. When the mismatch is severe, impairment of gas exchange results in abnormalities of arterial blood gases.

The total cross-sectional area of the pulmonary vascular bed is reduced in chronic bronchitis and emphysema as a result of anatomic changes and constriction of vascular smooth muscle in pulmonary arteries and arterioles as well as destruction of alveolar septa with loss of capillaries. Constriction of the pulmonary arterioles in response to alveolar hypoxia is also a major contributory factor. This constriction is reversible upon increase in alveolar PO2 with therapy. Acidosis due to respiratory failure augments pulmonary vessel constriction. Chronic hypoxia leads to secondary polycythaemia. This probably further adds to pulmonary hypertension by increasing blood viscosity. All these lead to pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy.

CAUSES :

- Smoking

- Occupational exposure to organic or inorganic dusts or noxious gases

- Air pollution – industrial effluents, smoke from wood fires

- Infections, especially viral lower respiratory infection in infancy

- Familial and genetic factor, e.g., alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

Smoking

Smoking is the most common single factor leading to chronic bronchitis. It impairs the mucociliary defence mechanisms of the lung and produces hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting glands. It also induces polymorphonuclear leucocyte injury by releasing proteolytic enzymes. Acute increase in airways resistance is also encountered following inhalation of smoke as a result of stimulation of submucous receptors and vagally-mediated smooth muscle constriction.

It is now well established that small airway obstruction is the earliest demonstrable mechanical defect in cigarette smokers and that obstruction may disappear on stopping smoking. Hooka and bidi smoking is just as harmful as cigarette smoking.

Passive, or Second-Hand, Smoking Exposure

Exposure of children to maternal smoking results in significantly reduced lung growth. In utero

tobacco smoke exposure also contributes to significant reductions in postnatal pulmonary function. Although passive smoke exposure has been associated with reductions in pulmonary function, the importance of this risk factor in the development of the severe pulmonary function reductions in COPD remains uncertain.

Occupational Exposures

Increased respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction have been suggested as resulting from general exposure to dust at work. Several specific occupational exposures, including coal mining, gold mining, and cotton textile dust, have been suggested as risk factors for chronic airflow obstruction. However, although nonsmokers in these occupations developed some reductions in FEV1, the importance of dust exposure as a risk factor for COPD, independent of cigarette smoking, is not certain. Among workers exposed to cadmium (a specific chemical fume), FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and DLCO were significantly reduced (FVC, forced vital capacity; DLCO, carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung; Chap. 234), consistent with airflow

obstruction and emphysema. Although several specific occupational dusts and fumes are likely risk factors for COPD, the magnitude of these effects appears to be substantially less important

than the effect of cigarette smoking.

Ambient Air Pollution

Some investigators have reported increased respiratory symptoms in those living in urban compared to rural areas, which may relate to increased pollution in the urban settings. However,

the relationship of air pollution to chronic airflow obstruction remains unproven. With high rates of COPD reported in nonsmoking women in many developing countries, indoor air pollution, usually associated with cooking, has been suggested as a potential contributor. In most populations, ambient air pollution is a much less important risk factor for COPD than cigarette smoking.

RespiratoryInfections

These have been studied as potential risk factors for the development and progression of COPD in adults; childhood respiratory infections have also been assessed as potential predisposing

factors for the eventual development of COPD. The impact of adult respiratory infections on decline in pulmonary function is controversial, but significant long-term reductions in pulmonary function are not typically seen following an episode of bronchitis or pneumonia. The impact of the effects of childhood respiratory illnesses on the subsequent development of COPD has been difficult to assess due to a lack of adequate longitudinal data. Thus, although respiratory infections are important causes of exacerbations of COPD, the association of both adult and childhood respiratory infections to the development and progression of COPD remains to be proven.

Familial and genetic factors

Familial aggregation of chronic bronchitis and emphysema may be due to overcrowding, indoor air pollution and passive smoking. Besides all these, studies of monozygotic twins have indicated a genetic predisposition to the development of chronic bronchitis.

Deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin, which is a protease inhibitor, is associated with the development of emphysema. Normal serum alpha-1 antitrypsin level is more than 250 mg/dl. The common genes associated with emphysema are the Z and S genes. Persons who are homozygous ZZ or SS have serum levels often near 0, but always less than 50 mg/dl. Such individuals develop severe panacinar emphysema. The MZ and MS heterozygotes have intermediate levels of serum alpha-1 antitrypsin, i.e., 50-250 mg/dl. The hereditary abnormality, however, accounts for only 3-5% of patients with chronic obstructive airways disease.

CLINICAL FEATURES :

- Dyspnoea

- Productive cough. Persistent cough producing yellow, white, or green phlegm.

- Decreased exercise tolerance.

- Wheeze

- Yellow, white, or green phlegm, usually appearing 24 to 48 hours after cough begins.

- Fever,chills.

- Soreness and tightness in chest.

Cough : Cough is usually the first symptom but seldom prompts the patient to consult a doctor. It is characteristically accompanied by small amounts of mucoid sputum. Chronic bronchitis is formally defined when a cough and sputum occur on most days for at least 3 consecutive months for at least 2 successive years. Haemoptysis may complicate exacerbations of COPD but should not be attributed to COPD without thorough investigation.(4)

Dyspnoea :

MODIFIED MRC DYSPNOEA SCALE

Grade Degree of breathlessness related to activities

0 No breathlessness except with strenuous exercise

1 Breathlessness when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill

2 Walks slower than contemporaries on level ground because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace

3 Stops for breath after walking about 100 m or after a few minutes on level ground

4 Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing or undressing

Wheeze : Wheezing is a whistling sound that occurs during breathing when the airways are narrowed. Commonly the sound is more prominent when you breathe out than when you breathe in (although not always). The sound is caused by air that is forced through airways that are narrower than normal. Narrowed airways can be due to:

- This means that the muscle within the lining of the airways contracts. This has an effect of narrowing (constricting) the airways.

- Swelling of the lining of the airways.

- A lot of secretions (mucus, etc) in the airways.

Chest tightness : Chest pain is common in patients with COPD, but is often unrelated to the disease itself, and may be due to underlying ischaemic heart disease or gastro-oesophageal reflux. Chest tightness is a common complaint during exacerbations of breathlessness, particularly during exercise, and this is sometimes difficult to distinguish from ischaemic cardiac pain. Pleuritic chest pain may suggest an intercurrent pneumothorax, pneumonia, or pulmonary infarction.

Fever ; Low grade fever may occasionally be present. A slight fever of 100 to 101°F with severe bronchitis. The fever may rise to 101 to 102°F and last three to five days even after antibiotics are started.

Signs depend on the severity of the underlying disease.

- Raised respiratory rate

- Hyperexpanded/barrel chest

- Prolonged expiratory time >5 seconds, with pursed lip breathing

- Use of accessory muscles of respiration

- Quiet breath sounds (especially in the lung apices) ± wheeze

- Quiet heart sounds (due to overlying hyperinflated lung)

- Possible basal crepitations

- Signs of cor pulmonale and CO2 retention (ankle oedema, raised JVP, warm peripheries, plethoric conjunctivae, bounding pulse, polycythaemia. Flapping tremor if CO2 acutely raised).

ACUTE EXACERBATION OF CHRONIC BRONCHITIS :

Exacerbations may cause mild symptoms in those with relatively preserved lung function, but may cause considerable morbidity in those with limited respiratory reserves. It has been increasingly recognized that significant numbers of patients do not regain their pre-morbid lung function or quality of life following an exacerbation. An exacerbation is essentially a clinical diagnosis.

Causes :

Causes may be infective organisms, either viral or bacterial, or non-infective causes, such as pollution or temperature changes. Common bacterial pathogens are Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis and the commonest viral pathogens are rhinovirus, influenza, coronavirus, and adenovirus.

Symptoms :

- Increased sputum volume and/or purulence,

- Increasing dyspnoea or wheeze,

- Chest tightness,

- Fluid retention.

INVESTIGATIONS :

SPUTUM EXAMINATION :

The sputum is usually mucoid and frothy and becomes mucopurulent or purulent during acute exacerbations. Sputum culture and sensitivity helps in management.

BLOOD EXAMINATION :

The white cell count may be raised. Polycythaemia is uncommon in Indian patients.

RADIOLOGICAL EXAMINATION :

The chest X-ray is not helpful in the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis. In emphysema, lungs are hyperinflated, diaphragms are flattened, heart appears long and small and peripheral vascular shadows may be thinned or lost as blood vessels are destroyed by advancing emphysema. On lateral film, overdistension may be shown by large retrosternal air space. Localised emphysematous bullae may be seen.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAM :

Electrocardiogram may be normal or may show low voltage in cases of emphysema. There may be clockwise rotation, right axis deviation and RS pattern in the chest leads extending to the left as far as V5 or V6. With the development of cor pulmonale, spiky P wave and prominent R wave in V1 may appear; T wave may be inverted from V1-V3 or there may be incomplete or complete right bundle branch block. Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias may be noted when associated with hypoxaemia.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS :

- Obstructive spirometry and flow-volume loops

- Reduced FEV1 to <80% predicted (FEV1 is the measurement of choice to assess progression of COPD)

- FEV1/FVC < 0.7

- Minimal bronchodilator reversibility (<15%, usually <10%)

- Raised total lung volume, FRC, and residual volume because of emphysema, air trapping, and loss of elastic recoil

- Decreased TLCO and kCO because presence of emphysema decreases surface area available for gas diffusion.

CXR is not required for diagnosis and repeated CXR is unnecessary unless other diagnoses are being considered (most importantly lung cancer or bronchiectasis).

- Hyperinflated lung fields with attenuation of peripheral vasculature—‘black lung sign’. More than 7 posterior ribs seen

- Flattened diaphragms (best CXR correlate of post-mortem degree of emphysema)

- More horizontal ribs

- May see bullae, especially in the lung apices, which if large can be mistaken for a pneumothorax due to the loss of lung markings (CT can differentiate).

Diagnosis is based on the history of smoking and progressive dyspnoea, with evidence of irreversible airflow obstruction on spirometry.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF STABLE COPD :

Aims of COPD management should include:

- ensuring the diagnosis is correct

- stopping smoking

- optimizing treatment by minimizing symptoms where possible

- helping the patient maintain their quality of life.

Management should be delivered by a multi-disciplinary team.

No treatment has yet been shown to modify disease progression in the long term, except for stopping smoking.

Smoking cessation is the only intervention that is proven to decrease the smoking-related decline in lung function. All patients with COPD who smoke should be encouraged to stop at every opportunity. The graph shows the accelerated decline in FEV1 in susceptible smokers and the delay in this acceleration from stopping smoking; susceptible smokers, however, never regain the original curve. Nicotine replacement therapy should be used to aid smoking cessation.

Education can improve ability to manage illness and stop smoking.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a multidisciplinary programme, with RCT evidence that it improves exercise tolerance, quality of life, and reduces hospital admissions. The mainstay of rehabilitation is graded exercise, but includes breathing techniques and education. Programmes vary, but are usually run on an out-patient basis over several weeks, with multidisciplinary involvement. Should be made available to all appropriate patients with COPD.

Diet :

Weight loss is recommended if the patient is obese, to minimize respiratory effort. If the patient is very breathless, calorific intake may be low and a catabolic state may exist. Nutritional supplementation may be necessary. Maintaining body weight and muscle mass correlates well with survival.

Prevention :

Avoidance of smoking, adequate control of atmospheric pollution in industry, use of ideal cooking fuel and prompt treatment of recurrent bronchopulmonary infections help in the prevention of this disease. Even in an established case, implementation of these measures helps in preventing further deterioration of lung function.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT :

Bronchodilator therapy is central to the management of breathlessness in patients with COPD. The inhaled route is preferred and a number of different agents delivered by a variety of devices are available. Choice should be informed by patient preference and inhaler assessment. Short-acting bronchodilators may be used for patients with mild disease but longer-acting bronchodilators are more appropriate for patients with moderate to severe disease. It is important to realise that significant improvements in breathlessness may be reported despite minimal changes in FEV1, probably reflecting improvements in lung emptying that reduce dynamic hyperinflation and ease the work of breathing.

Oral bronchodilator therapy may be contemplated in patients who cannot use inhaled devices efficiently. Theophylline preparations improve breathlessness and quality of life, but their use has been limited by side-effects, unpredictable metabolism and drug interactions. Bambuterol-a pro-drug of terbutaline-is used on occasion. Orally active highly selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors are currently being developed.

Corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations; they are currently recommended in patients with severe disease (FEV1 < 50%) who report two or more exacerbations requiring antibiotics or oral steroids per year. Regular use is associated with a small improvement in FEV1, but there is no impact on the accelerated decline in lung function. The combination of ICS with long-acting β2-agonists produces further improvement in breathlessness and reduces the frequency and severity of exacerbations.

Oral corticosteroids are useful during exacerbations but maintenance therapy contributes to osteoporosis and impaired skeletal muscle function and should be avoided. Oral corticosteroid trials may assist in the diagnosis of asthma but do not predict response to inhaled steroids in COPD.

Oxygen therapy

Long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy (LTOT) has been shown to improve survival, prevent progression of pulmonary hypertension, decrease the incidence of secondary polycythaemia, and improve neuropsychological health (Box 19.32). It is most conveniently provided by an oxygen concentrator via nasal prongs and patients should be instructed to use oxygen for a minimum of 15 hours/day; greater benefits are seen in patients who receive > 20 hours/day. The aim of therapy is to increase the PaO2 to at least 8 kPa (60 mmHg) or SaO2 at least 90% (Box 19.33). Ambulatory oxygen therapy should be considered in patients who desaturate on exercise and show objective improvement in exercise capacity and/or dyspnoea with oxygen. Oxygen flow rates should be adjusted to maintain SaO2 above 90%. Short-burst oxygen therapy is widely prescribed but is expensive and of unproven benefit.

Other measures :

Patients with COPD should be offered an annual influenza vaccination and, as appropriate, pneumococcal vaccination. Obesity, poor nutrition, depression and social isolation should be identified and, if possible, improved. Mucolytic therapy (e.g. acetylcysteine 200 mg orally 8-hourly for 8 weeks in the first instance) may be recommended in patients with chronic cough and sputum production and should be continued if symptomatic benefit is reported.

SURGICAL TREATMENT :

Lung transplant : In young patients (below 60–65), with severe disease, often due to α1-antitrypsin deficiency, single lung transplant may be an option. Local transplant teams will advise regarding local criteria.

Bullectomy : Suitable for selected patients with isolated bullae. Improves chest hyperinflation.

Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) :

Resection of areas of bullous emphysema to reduce chest hyperinflation, improve diaphragmatic function, elastic recoil, physiology of the lungs, and hence functional status of the patient. Patients who may be considered are those with FEV1 20-30% predicted, with symptomatic dyspnoea despite maximal medical therapy, and with heterogeneous areas of emphysema on CT, giving target areas to resect. Pre-operative assessment: PFTs, 6 minute walk test, quality of life, and dyspnoea indicators. Surgery is performed in specialist centres via median sternotomy or by thoracoscopy. Usually the upper lobe is stapled below the level of the emphysema and then removed. Improvements are seen in FEV1 and RV, dyspnoea, and quality of life scores. These effects are maximal between 2 and 6 months post-surgery. Symptomatic improvement is sustained for about 2-4 years. Post-operative complications: persistent air leak >7 days in 30-40%, pneumonia in up to 22%, respiratory failure in up to 13%. Post-operative mortality 2.4-17% reported.

The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (Michigan, USA) has shown that there is increased mortality from LVRS for patients with FEV1 or TLCO <20% predicted, or with homogeneous emphysema. They are also less likely to benefit from surgery. Surgery is not therefore recommended for this group. Trials are ongoing to fully assess which patients with COPD are most likely to benefit and to determine whether open thoracotomy or video-assisted minimally invasive surgery (VATS) is the most effective approach.

Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction is under evaluation, with valve implants placed within the segmental bronchi that supply the hyper-inflated lobes. It is a minimally invasive variation on lung volume reduction surgery, with the aim of improving lung function and quality of life.

COMPLICATIONS :

- Recurrent chest infections due to viruses and bacteria are seen.

- Pneumothorax may occur following a bout of cough.

- Respiratory failure and chronic cor pulmonale are end-stage complications.

- An increased incidence of peptic ulcer has been observed.

- The incidence of lung cancer is also higher, but this may be because lung cancer is also causally related to cigarette smoking.

Respiratory failure :

The later stages of COPD are characterized by the development of respiratory failure. For practical purposes this is said to occur when there is either a Pao2 of less than 8 kPa (60 mmHg) or a Paco2 of more than 7 kPa (55 mmHg).

The persistence of chronic alveolar hypoxia and hypercapnia leads to constriction of the pulmonary arterioles and subsequent pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiac output is normal or increased but salt and fluid retention occurs as a result of renal hypoxia.

Cor pulmonale :

Patients with advanced COPD may develop cor pulmonale, which is defined as heart disease secondary to disease of the lung. It is characterized by pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular hypertrophy, and eventually right heart failure. On examination, the patient is centrally cyanosed (owing to the lung disease) and, when heart failure develops, the patient becomes more breathless and ankle oedema occurs. Initially a prominent parasternal heave may be felt that is due to right ventricular hypertrophy and a loud pulmonary second sound may be heard. In very severe pulmonary hypertension there is incompetence of the pulmonary valve. With right heart failure, tricuspid incompetence may develop with a greatly elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP), ascites and upper abdominal discomfort owing to swelling of the liver.

COMPONENTS USED TO COMPUTE BMI, DEGREE OF AIRFLOW OBSTRUCTION AND DYSPNOEA, AND EXERCISE CAPACITY (BODE) INDEX

Points on BODE index

Variable 0 1 2 3

FEV1 ≥ 65 50-64 36-49 ≤ 35

Distance walked in 6 min (m) ≥ 350 250-349 150-249 ≤ 149

MMRC dyspnoea scale 0-1 2 3 4

Body mass index > 21 ≤ 21

A patient with a BODE score of 0-2 has a mortality rate of around 10% at 52 months whereas a patient with a BODE score of 7-10 has a mortality rate of around 80% at 52 months.

PROGNOSIS :

The prognosis is poor in patients having hypercapnia. Death generally occurs following a complication like fulminant chest infection, retained secretions with atelectasis, pneumothorax or respiratory failure.

COPD has a variable natural history. The prognosis is inversely related to age and directly related to the post-bronchodilator FEV1. Additional poor prognostic indicators include weight loss (survival is negatively correlated with BMI) and pulmonary hypertension. A recent study has suggested that a composite score comprising the body mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O), a measurement of dyspnoea (D) and exercise capacity (E) may assist in predicting death from respiratory and other causes.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF COPD :

- Asthma

- Bronchiectasis

- Bronchiolitis

- Left ventricular failure.

Miasm:

REPERTORY :

REPERTORY OF THE HOMOEOPATHIC MATERIA MEDICA- J.T.KENT

[CHEST – INFLAMMATION] – bronchial tubes (bronchitis): (85) Acet-ac. Acon. AESC. All-c. Alum. Alumn. am-c. Am-m. Ant-c. ANT-T. Apis Arn. ARS. ars-i. Asc-t. Aur-m. bar-c. BAR-M. Bell. Benz-ac. BRY. Cact. Calc. Camph. Cann-s. Carb-v. Carbn-s. card-m. Caust. Cham. Chel. chlol. chlor. Cina Cist. Coc-c. cop. dig. DROS. Dulc. euphr. Ferr-i. FERR-P. Gels. Guaj. HEP. Hippoz. Hyos. Iod. IP. kali-ar. Kali-bi. Kali-c. Kali-chl. kali-p. Kreos. Lach. Lob. LYC. Merc. Naja Nat-m. NAT-S. Nit-ac. Nux-v. Ph-ac. PHOS. Plb. Psor. PULS. Rhus-t. Rumx. SANG. SENEC. Seneg. Sep. SIL. SPONG. Squil. STANN. Sulph. Ter. uran-met. Verat. verb. (p. 835)

[RESPIRATION] DIFFICULT: (259) abies-n. abrot. absin. acet-ac. Acon. aesc. Aeth. Agar. Agn. ail. all-s. aloe alum. alumn. Am-c. am-m. Ambr. ANAC. Ant-ar. Ant-c. ANT-T. APIS apoc. Aral. arg-met. Arg-n. Arn. ARS. Ars-i. arum-t. arund. Asaf. Asar. Asc-t. aspar. astac. Aur. aur-m. aur-m-n. aur-s. Bad. bar-c. Bar-m. Bell. Benz-ac. bism. Blatta-o. borx. Bov. Brom. BRY. bufo CACT. cain. calad. Calc. Calc-ar. Calc-f. Calc-p. Calc-s. Camph. cann-i. cann-s. canth. Caps. carb-ac. carb-an. CARB-V. Carbn-o. Carbn-s. Carl. castm. CAUST. Cedr. Cench. Cham. CHEL. chen-a. CHIN. Chinin-ar. Chinin-s. chlol. CHLOR. Cic. cimic. Cimx. CINA cist. Coc-c. Coca Cocc. coff. Colch. coll. Coloc. Con. cop. cor-r. croc. Crot-c. Crot-h. CROT-T. Cub. CUPR. CUPR-AR. cupr-s. cur. Cycl. Dig. dirc. Dros. Dulc. equis-h. ery-a. eup-per. euph. euphr. FERR. Ferr-ar. Ferr-i. Ferr-p. Fl-ac. Gels. gins. Glon. Graph. Grin. Guaj. ham. Hell. HEP. hippoz. hura hydr. hydr-ac. hydrc. hyos. hyper. Ign. indg. Iod. IP. Iris jab. jatr-c. jug-c. KALI-AR. Kali-bi. KALI-C. Kali-chl. KALI-I. kali-n. Kali-p. Kali-s. Kalm. kreos. lac-c. LACH. Lact. Lat-m. Laur. led. Lil-t. Lith-c. LOB. LYC. Lycps-v. Lyss. mag-c. mag-m. mag-s. manc. mang. Med. meli. meny. MEPH. Merc. MERC-C. Merc-sul. merl. Mez. morph. Mosch. Mur-ac. murx. mygal. NAJA nat-act. Nat-c. Nat-m. Nat-p. NAT-S. nicc. Nit-ac. NUX-M. Nux-v. oena. ol-j. OP. osm. Ox-ac. par. petr. Ph-ac. phel. PHOS. Phys. Phyt. Plat. Plb. podo. Prun. Psor. ptel. PULS. Ran-b. ran-s. raph. rat. rheum rhod. Rhus-t. rumx. ruta sabad. sabin. Samb. Sang. sarr. sars. Sec. SEL. Seneg. Sep. SIL. Spig. SPONG. SQUIL. STANN. staph. Stram. STRY. sul-ac. SULPH. Tab. TARENT. tax. Ter. thuj. Tub. valer. VERAT. verat-v. vesp. viol-o. vip. Zinc. zing. (p. 766)

[GENERALS – EXERTION,physical,] – agg.: (125) acon. Agar. ALUM. Alumn. am-c. am-m. Ambr. Anac. ant-c. Ant-t. apis apoc. Arg-met. Arg-n. ARN. ARS. ARS-I. asaf. asar. aur. Bar-c. Benz-ac. Bol-la. borx. bov. BRY. Cact. CALC. Calc-p. CALC-S. Cann-s. Carb-v. Caust. Chel. Chin. chinin-ar. cic. cina COCC. coff. Colch. CON. croc. Crot-h. cycl. DIG. euphr. Ferr. Ferr-ar. FERR-I. ferr-p. GELS. graph. Guaj. Ham. hell. Helon. Hep. ign. IOD. ip. Kali-ar. Kali-bi. Kali-c. kali-n. Kali-p. kali-s. Kalm. Kreos. Lach. LAUR. led. lil-t. Lob. Lyc. Lycps-v. meny. Merc. Merc-c. Mur-ac. murx. naja NAT-ACT. NAT-C. NAT-M. nat-p. nit-ac. nux-m. Nux-v. olnd. Ox-ac. Ph-ac. Phos. PIC-AC. plat. Plb. Podo. Psor. Puls. Rheum rhod. RHUS-T. Ruta sabad. Sabin. Sang. sars. sec. SEL. SEP. Sil. sol-ni. SPIG. SPONG. squil. STANN. STAPH. sul-ac. SULPH. Tarent. thuj. Tub. Valer. verat. Zinc. (p. 1358)

[RESPIRATION] WHEEZING: (62) ail. aloe Alum. Ambr. Apoc. aral. arg-n. ARS. Ars-i. Brom. calad. calc. calc-s. Cann-s. Caps. CARB-V. carbn-s. Cham. Chin. Chinin-ar. chlol. Cina crot-t. Cupr. dol. Dros. ferr. ferr-i. Fl-ac. graph. hep. hydr-ac. Iod. IP. Kali-ar. Kali-bi. KALI-C. Kali-s. Lach. Lyc. Lycps-v. manc. merc. murx. naja Nat-m. Nat-s. Nit-ac. Nux-m. nux-v. ox-ac. phos. sabad. Samb. sang. sanic. sep. spong. squil. stann. sulph. Syph. (p. 776)

[EXPECTORATION] GREENISH: (79) anan. Arg-met. Arn. Ars. ars-i. arum-t. asaf. aur. benz-ac. borx. bov. bry. bufo cain. Calc. Calc-s. CALC-SIL. Cann-s. Carb-an. CARB-V. CARBN-S. coc-c. colch. Coloc. Cop. Crot-c. cub. cur. dig. dros. Dulc. eupi. Ferr. Ferr-ar. ferr-i. Ferr-p. ham. hyos. iod. kali-ar. Kali-bi. kali-c. KALI-I. kali-p. Kali-s. kreos. led. LYC. mag-c. Mang. med. MERC. Merc-i-f. Merc-i-r. Nat-c. nat-m. nat-p. NAT-S. nit-ac. nux-v. oena. ol-j. ox-ac. PAR. Petr. PHOS. plb. PSOR. PULS. raph. rhus-t. Sep. Sil. STANN. SULPH. syph. thuj. Tub. zinc. (p. 816)

[EXPECTORATION] WHITE: (91) Acon. Agar. ail. alum. Alumn. Am-br. am-c. am-m. ambr. ant-t. Apis apoc. Arg-met. arn. Ars. arund. aur-m. bar-c. Borx. bov. Calc. calc-s. caps. carb-ac. carb-an. Carb-v. Caust. cench. chin. chinin-ar. chinin-s. chlor. cina cob. Coc-c. crot-t. cupr. cur. dulc. eucal. ferr. ferr-ar. ferr-i. ferr-p. fl-ac. hyper. Iod. ip. Kali-bi. KALI-CHL. kali-i. kali-p. Kreos. Lac-c. laur. LYC. manc. Med. merc-i-r. mez. NAT-M. nicc. oena. ol-j. onos. ox-ac. par. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. phys. Puls. puls-n. raph. rhus-t. sacch. sang. Sel. senec. SENEG. SEP. sil. Spong. Squil. Stann. stront-c. Sulph. syph. tarent. tell. thuj. (p. 820)

[EXPECTORATION] YELLOW: (135) Acon. ail. aloe alum. am-c. Am-m. ambr. anac. anan. Ang. ant-c. arg-met. Arg-n. Ars. Ars-i. arum-m. arum-t. asc-t. astac. aur. aur-m. aur-s. Bad. bar-c. bar-m. bell. bism. borx. bov. brom. Bry. bufo Cact. CALC. CALC-P. CALC-S. cann-s. Canth. carb-an. Carb-v. carbn-s. caust. cench. cham. chlol. cic. cist. Coc-c. coca coloc. con. cop. cub. cupr. daph. dig. Dros. eug. eupi. ferr. ferr-ar. ferr-i. Ferr-p. graph. ham. HEP. hura HYDR. hydr-ac. Ign. iod. ip. kali-ar. Kali-bi. Kali-c. Kali-chl. Kali-p. Kali-s. Kreos. lac-ac. lach. linu-c. LYC. mag-c. mag-m. mang. med. Merc. merc-i-f. Merc-i-r. mez. mur-ac. Nat-act. Nat-c. nat-m. Nat-p. Nit-ac. nux-v. oena. Ol-j. op. ox-ac. par. Petr. Ph-ac. PHOS. phyt. plb. Psor. PULS. pyrog. rumx. Ruta sabad. sacch. samb. sang. Sanic. sel. senec. seneg. SEP. SIL. spig. Spong. STANN. Staph. sul-ac. Sulph. syph. tarent. Thuj. TUB. verat. Zinc. (p. 821)

[FEVER] CHILL,with: (65) ACON. ambr. anac. ant-c. ARS. ars-i. asar. BELL. benz-ac. Bry. bufo CALC. caps. carb-v. CHAM. chel. chin. Chinin-s. Cocc. coff. coloc. Dig. Dros. Ferr. ferr-ar. Graph. HELL. IGN. iod. ip. kali-ar. kreos. Led. lyc. Merc. Mez. nat-c. nat-m. Nat-s. nicc. NIT-AC. NUX-V. Olnd. petr. phos. Plb. Podo. Puls. Pyrog. ran-b. RHUS-T. sabad. sabin. Samb. Sang. Sep. sil. spig. staph. Stram. SULPH. Tarent. Thuj. Verat. Zinc. (p. 1284)

[CHEST – PAIN] – sore,bruised: (126) acon. aesc. agar. alum. Am-m. ambr. anac. ant-t. APIS ARN. Ars. arum-t. asc-t. Bad. bapt. bar-c. berb. brom. BRY. CALC. calc-p. calc-s. canth. carb-an. Carb-v. Carbn-s. CAUST. cham. CHEL. CHIN. chlor. Cic. cimic. Cina Coc-c. cocc. colch. Cop. corn. crot-t. Cur. dig. dor. echi. Euon. Eup-per. Ferr. ferr-ar. ferr-m. ferr-p. fl-ac. gamb. Gels. graph. Guaj. Ham. HEP. Hydr. Hyos. ign. ip. iris kali-ar. KALI-BI. Kali-c. kali-n. kali-p. kali-s. Kreos. Lac-d. Lach. lact. laur. Led. lob. Lyc. lyss. Mag-c. Mag-m. manc. mang. med. meph. Merc. Mez. Mur-ac. nat-act. Nat-c. Nat-m. nat-p. nat-s. nicc. Nit-ac. Nux-m. nux-v. ol-j. olnd. ox-ac. Petr. PHOS. Phyt. psor. PULS. RAN-B. ran-s. rat. rhod. Rhus-t. rumx. samb. sang. sanic. SENEG. Sep. Sil. Spong. STANN. Staph. stront-c. sul-ac. Sulph. syph. tab. tarent. thuj. Zinc. (p. 860)

[CHEST] CONSTRICTION,tension,tightness: (187) ACON. Aesc. Agar. ail. All-c. Alum. alumn. am-c. am-m. ambr. anac. Ang. Ant-t. apis aral. Arg-n. Arn. ARS. Ars-h. Ars-i. Asaf. asar. asc-t. aspar. AUR. Aur-m. Bapt. Bar-c. BELL. bism. Borx. bov. BROM. BRY. bufo CACT. Cadm-s. cain. CALC. Calc-p. calc-s. Camph. cann-i. cann-s. canth. Caps. Carb-ac. Carb-an. CARB-V. Carbn-o. CARBN-S. carl. CAUST. Cham. CHEL. chin. chinin-ar. chlol. Chlor. Cic. Cimx. cina cinnb. clem. Coc-c. Cocc. coff. Colch. Coloc. CON. cop. Crot-c. crot-h. Crot-t. Cupr. cupr-s. cycl. Dig. dios. Dros. Dulc. elaps Euph. Ferr. ferr-ar. ferr-i. ferr-p. gamb. Gels. gins. Glon. GRAPH. Hell. Hep. hydr-ac. Hyos. Hyper. ictod. IGN. Iod. Ip. iris jatr-c. Kali-ar. Kali-bi. Kali-c. Kali-chl. kali-i. Kali-n. kali-p. kali-s. kreos. LACH. Lact. Laur. lec. Led. lith-c. LOB. LYC. Lycps-v. Mag-c. Mag-m. Mag-p. Manc. mang. Merc. Merc-c. merc-i-r. Mez. morph. mosch. mur-ac. Naja Nat-act. Nat-c. NAT-M. nat-p. Nit-ac. Nux-m. Nux-v. olnd. Op. osm. ox-ac. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. phys. pic-ac. Plat. plb. podo. psor. Puls. rat. Rhod. Rhus-t. ruta sabin. samb. Sars. SENEG. Sep. SIL. Spig. Spong. squil. STANN. Staph. Stram. stront-c. stry. sul-ac. sul-i. SULPH. sumb. Tab. tarent. ter. thea thuj. upa. VERAT. verb. xan. zinc. (p. 826)

BOENNINGHAUSEN’S THERAPEUTIC POCKET BOOK T.F.ALLEN

[Parts of the body and organs – Respiration] – suffocation; attacks of: (73) ACON. anac. Ant-c. ANT-T. ARS. asar. Aur. bar-c. Bell. BRY. Calc. Camph. Cann-s. canth. Carb-an. CARB-V. caust. CHAM. CHIN. cic. cina cocc. Coff. Con. Cupr. Cycl. Dig. DROS. euphr. Ferr. GRAPH. Hell. HEP. Hyos. IGN. IOD. IP. kali-n. kreos. Lach. Laur. Led. Lyc. M-ARCT. m-aust. mag-m. merc. mosch. nat-m. nit-ac. nux-m. NUX-V. OP. petr. PHOS. Plat. plb. PULS. ran-b. rhus-t. sabad. SAMB. Sec. Seneg. sep. sil. Spig. SPONG. Stann. Staph. stram. SULPH. VERAT. (p. 114)

[Parts of the body and organs – Cough] – expectoration; with: (106) acon. Agar. agn. alum. am-c. Am-m. Ambr. anac. ang. ant-c. Ant-t. ARG-MET. arn. ARS. asaf. Asar. aur. Bar-c. bell. BISM. borx. Bov. BRY. Calad. CALC. Cann-s. canth. caps. Carb-an. Carb-v. Caust. Cham. CHIN. CIC. Cina cocc. colch. coloc. con. croc. cupr. dig. DROS. Dulc. euph. Euphr. FERR. Graph. Guaj. Hep. hyos. ign. IOD. ip. KALI-C. kali-n. KREOS. lach. laur. Led. LYC. m-ambo. M-aust. Mag-c. mag-m. Mang. merc. mez. mur-ac. Nat-c. nat-m. nit-ac. nux-m. Nux-v. olnd. op. Par. petr. PH-AC. PHOS. Plb. PULS. rheum rhod. Rhus-t. RUTA sabad. sabin. Samb. sec. sel. SENEG. SEP. SIL. spig. Spong. SQUIL. STANN. Staph. stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. tarax. THUJ. Verat. Zinc. (p. 115)

[Parts of the body and organs – Respiration] – rattling (with mucous râle): (50) Acon. alum. am-c. anac. Ang. ant-c. ANT-T. Arn. Ars. Bell. Bry. Calc. camph. cann-s. Carb-an. carb-v. Caust. CHAM. CHIN. Cina cocc. croc. CUPR. ferr. HEP. HYOS. ign. IP. kali-c. lach. LAUR. Led. LYC. merc. nat-c. Nat-m. nit-ac. Nux-v. OP. par. Petr. Phos. puls. Samb. sep. Spong. squil.

STANN. STRAM. Sulph. (p. 113)

[Change of general state – Aggravation – exertion; from] . body; of: (70) ACON. agar. Alum. am-c. am-m. ambr. ant-c. ARN. ARS. asaf. asar. Aur. borx. bov. BRY. CALC. CANN-S. caust. chin. cic. cina COCC. Coff. colch. con. Croc. euphr. ferr. graph. hell. Hep. ign. Iod. Ip. kali-n. kreos. lach. led. LYC. Merc. mur-ac. Nat-c. NAT-M. Nit-ac. Nux-m. NUX-V. Olnd. Phos. plat. puls. RHEUM Rhod. RHUS-T. RUTA sabad. SABIN. sars. sec. Sep. SIL. spig. Spong. Squil. stann. staph. sul-ac. SULPH. thuj. Verat. ZINC. (p. 280)

[Parts of the body and organs – Cough – expectoration] . greenish: (34) Ars. asaf. aur. borx. bov. calc. cann-s. carb-an. Carb-v. colch. dros. Ferr. hyos. iod. kali-c. Kreos. Led. lyc. m-aust. mang. merc. Nat-c. nit-ac. nux-v. PAR. Phos. plb. PULS. rhus-t. SEP. sil. Stann. sulph. thuj.(p. 118)

[Parts of the body and organs – Cough – expectoration] . whitish: (18) Acon. Am-m. ambr. ARG-MET. Cina Kreos. laur. LYC. par. Ph-ac. PHOS. rhus-t. SEP. sil. spong. Squil. stront-c. Sulph.(p. 119)

[Parts of the body and organs – Cough – expectoration] . yellow: (66) ACON. Alum. am-c. AM-M. ambr. anac. ang. ant-c. arg-met. ARS. Aur. Bar-c. bell. Bism. borx. Bov. BRY. CALC. carb-an. CARB-V. caust. cham. cic. con. Dig. dros. graph. hep. ign. Iod. ip. Kali-c. KREOS. LYC. Mag-c. mag-m. Mang. MERC. mez. mur-ac. NAT-C. Nat-m. Nit-ac. nux-v. op. par. ph-ac. PHOS. plb. PULS. ruta Sabad. sabin. Sel. seneg. SEP. sil. spig. SPONG. STANN. STAPH. Sul-ac. Sulph. THUJ. Verat. Zinc. (p. 119)

[Fever – Chill] – general; in: (123) Acon. Agar. agn. ALUM. AM-C. am-m. AMBR. Anac. ang. ant-c. ANT-T. Arg-met. ARN. ARS. Asar. aur. bar-c. Bell. bism. borx. BOV. BRY. CALAD. CALC. camph. cann-s. CANTH. CAPS. CARB-AN. Carb-v. Caust. CHAM. Chel. CHIN. cic. Cina clem. Cocc. coff. COLCH. coloc. Con. Croc. cupr. cycl. dig. Dros. dulc. euph. euphr. ferr. GRAPH. guaj. Hell. HEP. hyos. IGN. iod. Ip. Kali-c. Kali-n. KREOS. lach. Laur. Led. LYC. m-ambo. M-arct. m-aust. Mag-c. mag-m. Mang. meny. MERC. MEZ. mosch. Mur-ac. Nat-c. NAT-M. Nit-ac. NUX-M. NUX-V. olnd. op. Par. Petr. Ph-ac. PHOS. Plat. Plb. PULS. RAN-B. ran-s. rheum rhod. RHUS-T. ruta Sabad. sabin. samb. SARS. sec. sel. seneg. SEP. SIL. SPIG. Spong. Squil. stann. STAPH. stram. stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. Tarax. Teucr. Thuj. valer. VERAT. verb. viol-t. Zinc.(p. 254)

[Sensations and complaints – External parts of body and internal organs in general – sore pain (smarting)] . External parts; of: (99) ALUM. am-c. am-m. Ambr. Anac. ang. ANT-C. Arg-met. ARN. Ars. asaf. Aur. Bar-c. Bell. bism. Borx. Bov. BRY. calad. CALC. camph. cann-s. Canth. carb-an. Carb-v. CAUST. Cham. Chin. CIC. cina Clem. coff. Colch. coloc. Con. croc. cupr. Cycl. Dig. Dros. Euph. euphr. ferr. GRAPH. HEP. hyos. IGN. Iod. ip. KALI-C. kreos. led. Lyc. M-ambo. M-arct. M-aust. mag-c. Mag-m. Mang. Meny. MERC. MEZ. mosch. Mur-ac. Nat-c. NAT-M. nit-ac. NUX-V. olnd. par. petr. Ph-ac. PHOS. PLAT. plb. PULS. Ran-b. Rhod. RHUS-T. Ruta sabad. sabin. sars. sec. SEP. Sil. spig. spong. squil. stann. STAPH. stront-c. SUL-AC. SULPH. teucr. Thuj. valer. Verat. ZINC. (p. 181)

[Sensations and complaints – External parts of body and internal organs in general – sore pain (smarting)] . External parts; of: (99) ALUM. am-c. am-m. Ambr. Anac. ang. ANT-C. Arg-met. ARN. Ars. asaf. Aur. Bar-c. Bell. bism. Borx. Bov. BRY. calad. CALC. camph. cann-s. Canth. carb-an. Carb-v. CAUST. Cham. Chin. CIC. cina Clem. coff. Colch. coloc. Con. croc. cupr. Cycl. Dig. Dros. Euph. euphr. ferr. GRAPH. HEP. hyos. IGN. Iod. ip. KALI-C. kreos. led. Lyc. M-ambo. M-arct. M-aust. mag-c. Mag-m. Mang. Meny. MERC. MEZ. mosch. Mur-ac. Nat-c. NAT-M. nit-ac. NUX-V. olnd. par. petr. Ph-ac. PHOS. PLAT. plb. PULS. Ran-b. Rhod. RHUS-T. Ruta sabad. sabin. sars. sec. SEP. Sil. spig. spong. squil. stann. STAPH. stront-c. SUL-AC. SULPH. teucr. Thuj. valer. Verat. ZINC. (p. 153)

[Parts of the body and organs – Respiration] – fast, accelerated: (92) ACON. agar. alum. Am-c. ambr. anac. Ant-t. Arn. ARS. Asaf. asar. Aur. bar-c. BELL. borx. bov. BRY. Calc. Camph. cann-s. canth. carb-an. CARB-V. caust. Cham. Chin. cic. Cina Cocc. coff. coloc. con. CUPR. Cycl. dig. dros. Euph. euphr. ferr. guaj. HEP. hyos. IGN. IP. Kali-c. kali-n. Kreos. lach. laur. led. LYC. m-arct. m-aust. mag-c. mag-m. Merc. Mez. mosch. NAT-C. NAT-M. nit-ac. nux-m. NUX-V. Op. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. Plat. plb. PULS. Ran-b. Rhod. RHUS-T. ruta sabad. sabin. Samb. sars. sec. SENEG. SEP. SIL. Spig. spong. Squil. STANN. staph. stram. SULPH. VERAT. viol-o. Zinc. (p. 113)

BOGER BOENNINGHAUSEN’S CHARACTERISTICS & REPERTORY C.M.BOGER

[CHEST – Inner] – bronchia bronchitis, etc.: (49) ACON. ant-t. Arn. ARS. bar-c. BELL. BRY. Calc. CAPS. CARB-V. Caust. CHAM. CHIN. Cina con. DROS. DULC. Euphr. ferr. HEP. HYOS. Ign. Ip. Kali-bi. Lach. lyc. mag-c. mang. MERC. nat-c. nat-m. NUX-V. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. PULS. RHUS-T. sabad. Sep. Sil. SPIG. SPONG. squil. STANN. Staph. stram. SULPH. Verat. VERB. (p. 755)

[RESPIRATION] Difficult: (93) ACON. Agar. ALUM. am-c. am-m. Ang. ant-c. Ant-t. apis arg-met. arg-n. Arn. ARS. asaf. asar. Aur. bar-c. BELL. Bism. BRY. calad. Calc. CAMPH. Canth. Caps. CARB-V. caust. chel. Chin. Cic. cina COCC. Colch. con. croc. Crot-t. CUPR. Cycl. dig. dros. euphr. Ferr. graph. guaj. Hell. HEP. HYOS. ign. IOD. Kali-bi. KALI-C. KREOS. LACH. Laur. Led. LYC. mag-c. Merc. mez. mosch. naja NAT-C. Nux-m. Nux-v. Op. ph-ac. PHOS. PLAT. Plb. prun. Puls. RAN-B. rhod. Rhus-t. Sabad. sars. SEC. sel. Seneg. sep. sil. spig. SPONG. Squil. STANN. staph. Stram. SULPH. tab. tarax. valer. VERAT. VIOL-O. (p. 691)

[RESPIRATION] Obstructed, arrested, asphyxia, etc.: (79) acon. alum. am-c. Anac. ant-t. Arn. ARS. bar-c. Bell. bism. borx. BRY. calad. CALC. camph. canth. caps. carb-an. carb-v. Caust. cham. Chin. cina Cocc. coff. croc. Cupr. dros. euphr. grat. guaj. hep. HYDR-AC. ign. ip. Kali-c. kali-n. kreos. LACH. Laur. Led. Lyc. mag-m. merc. mosch. mur-ac. nat-m. nit-ac. Nux-m. Nux-v. Op. petr. Phos. Plat. Plb. Puls. ran-b. ran-s. rhus-t. Ruta sabad. sabin. samb. Sars. sel. sep. SIL. spig. spong. squil. STANN. staph. Stram. sul-ac. SULPH. tarax. valer. Verat. verb. (p. 692)

[CONDITIONS OF AGGRAVATION AND AMELIORATION IN GENERAL – Exertion – physical] . agg.: (73) ACON. agar. Alum. am-c. am-m. ambr. ant-c. ARN. ARS. asaf. asar. Aur. borx. bov. brom. BRY. CALC. calc-p. Caust. CHIN. cic. cina COCC. Coff. colch. con. Croc. DIG. euphr. ferr. fl-ac. graph. hell. Hep. ign. Iod. Ip. kali-n. kreos. lach. LYC. Lycps-v. Merc. mur-ac. Nat-c. NAT-M. Nit-ac. NUX-V. Olnd. PHOS. plat. puls. RHEUM Rhod. RHUS-T. RUTA sabad. SABIN. sars. sec. Sep. SIL. spig. Spong. Squil. stann. staph. Stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. thuj. VERAT. ZINC. (p. 1117)

[COUGH – Expectoration] – with: (105) ACON. Agar. agn. ALUM. am-c. Am-m. Ambr. ANAC. ang. ant-c. Ant-t. Arg-met. arn. ARS. asaf. Asar. aur. Bar-c. BELL. Bism. borx. Bov. BRY. Calad. CALC. canth. caps. carb-an. CARB-V. Caust. Cham. CHIN. Cic. Cina cocc. colch. coloc. con. croc. cupr. DIG. DROS. Dulc. euph. Euphr. Ferr. Graph. Guaj. Hep. hyos. ign. IOD. ip. KALI-BI. KALI-C. kali-n. KREOS. lach. LAUR. LED. LYC. mag-c. mag-m. Mang. Meph. Merc. mez. mur-ac. nat-c. Nat-m. nit-ac. nux-m. Nux-v. olnd. op. par. petr. Ph-ac. PHOS. Plb. PULS. rheum rhod. Rhus-t. Ruta sabad. sabin. Samb. sec. sel. SENEG. SEP. SIL. spig. SPONG. SQUIL. STANN. STAPH. stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. tarax. THUJ. VERAT. Zinc. (p. 727)

[COUGH – Expectoration] – greenish: (37) ARS. asaf. aur. borx. Bov. bry. bufo calc. carb-an. CARB-V. Colch. DROS. ferr. hyos. iod. kali-bi. kali-c. Kreos. Led. LYC. MAG-C. Mang. merc. Nat-c. nit-ac. nux-v. ol-j. par. PHOS. plb. PULS. rhus-t. Sep. Sil. STANN. SULPH. THUJ. (p. 729)

[COUGH – Expectoration] – whitish: (27) ACON. Am-m. ambr. ARG-MET. aur-m. carb-an. CARB-V. chin. cina cupr. ferr. kali-bi. KREOS. laur. LYC. naja par. ph-ac. PHOS. PULS. rhus-t. SEP. sil. spong. Squil. stront-c. SULPH. (p. 731)

[COUGH – Expectoration] – yellow: (70) acon. Alum. am-c. am-m. ambr. anac. ang. ant-c. arg-met. ars. aur. Bar-c. Bell. Bism. borx. Bov. BRY. CALC. carb-an. CARB-V. caust. cham. chlor. cic. Con. Dig. DROS. graph. hep. ign. Iod. ip. kali-bi. Kali-c. KALI-I. KREOS. Lyc. mag-c. mag-m. mang. Merc. mez. mur-ac. nat-c. Nat-m. NIT-AC. nux-v. ol-j. op. Par. ph-ac. PHOS. plb. PULS. RUTA Sabad. sabin. Sel. seneg. SEP. sil. spig. SPONG. STANN. STAPH. Sul-ac. SULPH. THUJ. verat. Zinc. (p. 731)

[RESPIRATION] Tight, wheezing: (95) Acon. Agar. aloe Alum. Am-c. anac. Ang. Apis arg-met. arg-n. arn. ARS. ASAF. AUR. BELL. Bov. brom. bry. Calad. CALC. camph. caps. carb-an. carb-v. Caust. Cham. CHIN. CIC. cina COCC. coloc. con. croc. CUPR. DIG. dros. Dulc. euphr. Ferr. fl-ac. Form. Hell. Hep. HYOS. ign. IOD. IP. kali-bi. kali-c. KALI-I. kali-n. LACH. Laur. LED. lyc. mag-m. MERC. mez. Mosch. Mur-ac. NAT-M. NAT-N. NAT-S. Nit-ac. nux-m. Nux-v. Op. par. Ph-ac. phos. plb. PULS. ran-b. ran-s. RHOD. rhus-t. ruta Sabad. samb. sars. SENEG. sep. SIL. SPONG. squil. Stann. Staph. stram. sul-ac. SULPH. teucr. THUJ. VERAT. VISC. ZINC. (p. 694)

[CHEST – Heart and region of] – soreness: (29) acon. apis Arn. Ars. bar-c. bell. Cimic. cinnb. colch. crot-h. elaps Fl-ac. gels. hyos. ign. kali-bi. Lach. laur. Lith-c. Lycps-v. mag-c. Nat-m. ol-an. ox-ac. samb. sec. sul-ac. Tab. thuj. (p. 760)

[CHEST – Heart and region of] – tension, tightness, etc.: (21) Ars. bar-c. bry. caust. Colch. con. ferr. hyos. Kali-c. kreos. nat-m. plat. prun. puls. rhus-t. sabin. sec. stann. sulph. thuj. Zinc. (p. 762)

[RESPIRATION] Quickened, rapid: (92) ACON. agar. alum. Am-c. ambr. anac. Ant-t. arn. Ars. Asaf. asar. aur. bar-c. BELL. borx. bov. BRY. calc. camph. canth. carb-an. CARB-V. caust. cham. chin. cic. CINA cocc. coff. coloc. con. CUPR. Cycl. dig. dros. Euph. euphr. ferr. guaj. hell. HEP. hyos. Ign. IOD. IP. kali-bi. kali-c. kali-n. kreos. lach. LAUR. led. LYC. mag-c. mag-m. merc. mez. mosch. Nat-c. Nat-m. nit-ac. nux-m. NUX-V. op. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. Plat. plb. PULS. Ran-b. rhod. Rhus-t. ruta sabad. sabin. SAMB. sars. sec. Seneg. SEP. Sil. spig. SPONG. squil. Stann. staph. stram. SULPH. VERAT. viol-o. zinc. (p. 693)

[RESPIRATION] Crepitation: (16) ant-t. bell. carb-an. carb-v. caust. cupr. hep. hyos. ip. laur. nat-m. puls. samb. sep. sil. squil. (p. 691)

DIFFERENTIATION OF REMEDIES :

Homeopathic medicines commonly used in the case of chronic bronchitis are as follows :

Antimonium tartaricum:

This remedy is indicated when the person has a feeling of wet mucus in the chest, and breathing makes a bubbly, rattling sound. The cough takes effort and is often not quite strong enough to bring the mucus up, although burping and spitting may be of help. The person may feel drowsy or dizzy, and feel better when lying on the right side or sitting up.

Bryonia:

This remedy is often indicated when a cough is dry and very painful. The person feels worse from any movement, and may even need to hold his or her sides or press against the chest to keep it still. The cough can make the stomach hurt, and digestion may be upset. A very dry mouth is common, and the person may be thirsty. A person who wants to be left alone when ill, and not talked to or disturbed, is likely to need Bryonia.

Calcarea carbonica:

This remedy is often indicated forbronchitis after a cold. The cough can be troublesome and tickling, worse from lying down or stooping forward, worse from getting cold, and worse at night. Children may have fever, sweaty heads while sleeping, and be very tired. Adults may feel more chilly and have clammy hands and feet, breathing problems when walking up slopes or climbing stairs, and generally poor stamina.

Causticum:

Bronchitis with a deep, hard, racking cough can indicate a need for this remedy. The person fees that mucus is stuck in the throat and upper chest, and may cough continually to try to loosen it. A feeling of rawness and soreness can develop, or a sensation as if a rock is stuck inside. Chills can occur along with fever. Exposure to cool air aggravates the cough, but drinking something cold can help. The person may feel worse when days are cold and clear, and better in wet weather.

Dulcamara:

When a person easily gets ill after being wet and chilled (or when the weather changes from warm and dry to wet and cool) this remedy may be indicated. The cough can be tickly, hoarse, and loose, and worse from physical exertion. Tendencies toward allergies (cats, pollen, etc.) may increase the person’s susceptibility to bronchitis.

Hepar sulphuris calcareum:

The cough that fits this remedy is usually hoarse and rattling, with yellow mucus coming up. The person can be extremely sensitive to cold—even a minor draft or sticking an arm out from under the covers may set off jags of coughing. Cold food or drink can make things worse. A person who needs this remedy feels vulnerable both physically and emotionally, and may act extremely irritable and out of sorts.

Kali bichromicum:

A metallic, brassy, hacking cough that starts with a troublesome tickling in the upper air-tubes and brings up strings of sticky yellow mucus can indicate this remedy. A sensation of coldness may be felt inside the chest, and coughing can lead to pain behind the breastbone or extending to the shoulders. Breathing may make a rattling sound when the person sleeps. Problems are typically worse in the early morning, after eating and drinking, and from exposure to open air. The person feels best just lying in bed and keeping warm.

Pulsatilla:

Bronchitis with a feeling of weight in the chest, and a cough with choking and gagging that brings up thick yellow mucus, may respond to this remedy. The cough tends to be dry and tight at night, and loose in the morning. The fever may be worse in the evening and at night. Feeling too warm or being in a stuffy room tends to make the person worse, and open air brings improvement. Thirst is usually low. A person who needs this remedy often is moody and emotional and wants attention and sympathy. (This remedy is often helpful to children who are tearful when not feeling well and want to be held and comforted.)

Silicea (also called Silica):

A person who needs this remedy can have bronchitis for weeks at a stretch, or even all winter long. The cough takes effort and may bring up yellow or greenish mucus, or little granules that have an offensive smell. Stitching pains may be felt in the back when the person is coughing. Chills are felt more than heat during fever, and the person is likely to sweat at night. A person who needs this remedy is usually sensitive and nervous, with low stamina, swollen lymph nodes, and poor resistance to infection.

Sulphur:

This remedy can be indicated when a person has had many bouts of bronchitis (sometimes the resistance has been weakened by taking antibiotics too often for minor complaints). The cough feels irritating, burning, and painful; yellow or greenish mucus may be produced. Problems can be worse if the person gets too warm in bed, and breathing problems at night may wake the person up. Redness of the eyes and mucous membranes, and foul-smelling breath and perspiration are often seen when a person needs this remedy.