APPENDICITIS

Introduction:

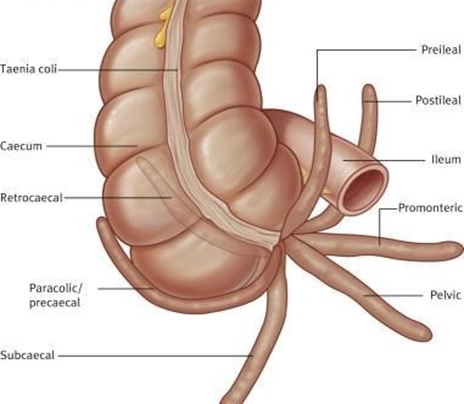

Appendix is also called as vermiform appendix or caecal appendix or vermix. It is a blind-ended tube connected to the cecum, from which it develops embryologically. The cecum is a pouch-like structure of the colon. The appendix is located near the junction of the small intestine and the large intestine.

INCIDENCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY :

The peak incidence of acute appendicitis is in the second and third decades of life; it is relatively rare at the extremes of age. Males and females are equally affected, except between puberty and age 25, when males predominate in a 3:2 ratio. Perforation is more common in infancy and in the aged, during which periods mortality rates are highest. Although various factors such as changing dietary habits, altered intestinal flora, and better nutrition and intake of vitamins have been suggested to explain the reduced incidence, the exact reasons have not been elucidated. The overall incidence of appendicitis is much lower in underdeveloped countries, especially parts of Africa, and in lower socioeconomic groups.

ETIOLOGY:

In developing countries that are adopting a more refined western-type diet, the incidence continues to rise. This is in contrast to the dramatic decrease in the incidence of appendicitis in western countries observed in the past 30 years. No reason has been established for these paradoxical changes; however, improved hygiene and a change in the pattern of childhood gastrointestinal infection related to the increased use of antibiotics may be responsible.

While appendicitis is clearly associated with bacterial proliferation within the appendix, no single organism is responsible. A mixed growth of aerobic and anaerobic organisms is usual. The initiating event causing bacterial proliferation is controversial. Obstruction of the appendix lumen has been widely held to be important, and some form of luminal obstruction, either by a faecolith or a stricture, is found in the majority of cases. A faecolith is composed of inspissated faecal material, calcium phosphates, bacteria and epithelial debris. Rarely, a foreign body is incorporated into the mass. The incidental finding of a faecolith is a relative indication for prophylactic appendicectomy. A fibrotic stricture of the appendix usually indicates previous appendicitis that resolved without surgical intervention. Obstruction of the appendiceal orifice by tumour, particularly carcinoma of the caecum, is an occasional cause of acute appendicitis in middle-aged and elderly patients. Intestinal parasites, particularly Oxyuris vermicularis (pinworm), can proliferate in the appendix and occlude the lumen.

PATHOGENESIS :

Luminal obstruction has long been considered the pathogenetic hallmark. However, obstruction can be identified in only 30 to 40% of cases; ulceration of the mucosa is the initial event in the majority. The cause of the ulceration is unknown, although a viral etiology has been postulated. Infection with Yersinia organisms may cause the disease, since high complement fixation antibody titers have been found in up to 30% of cases of proven appendicitis. Whether the inflammatory reaction seen with ulceration is sufficient to obstruct the tiny appendiceal lumen even transiently is not clear. Obstruction, when present, is most commonly caused by a fecalith, which results from accumulation and inspissation of fecal matter around vegetable fibers. Enlarged lymphoid follicles associated with viral infections (e.g., measles), inspissated barium, worms (e.g., pinworms, Ascaris, and Taenia), and tumors (e.g., carcinoid or carcinoma) may also obstruct the lumen. Secretion of mucus distends the organ, which has a capacity of only 0.1 to 0.2 mL, and luminal pressures rise as high as 60 cmH2O.

Luminal bacteria multiply and invade the appendiceal wall as venous engorgement and subsequent arterial compromise result from the high intraluminal pressures. Finally, gangrene and perforation occur. If the process evolves slowly, adjacent organs such as the terminal ileum, caecum, and omentum may wall off the appendiceal area so that a localized abscess will develop, whereas rapid progression of vascular impairment may cause perforation with free access to the peritoneal cavity.

TYPES OF APPENDICITIS:

This can be categorized as under:

- Acute appendicitis: This appears suddenly, and runs a short course, calling for urgent attention and treatment; mostly surgical treatment.

- Chronic appendicitis: As the name suggests, it is a long standing inflammation of the appendix.

- Recurring appendicitis: Appendix, if not removed, may have a tendency to get inflamed and infected, again and again.(12)

CHRONIC APPENDICITIS :

It is a sequel of acute appendicitis. In some patients the symptoms of appendicitis, are less intense and continue for a long duration, they may be continuous or intermittent. They may present as pain in the abdomen, which will be bothersome but not incapacitating. The person may experience pain and abdominal discomfort in the right iliac fossa.A partial obstruction of the appendix and milder bacterial infection are generally responsible. They may settle down with a course of antibiotics, but resurface again. This also indicates a lowered immune system.(12)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS :

Most patients present with abdominal pain; in many it starts vaguely in the centre of the abdomen, becoming localized to the right iliac fossa in the first few hours. Nausea, vomiting, anorexia and occasional diarrhoea can occur.

The history and sequence of symptoms are important diagnostic features of appendicitis. The initial symptom is almost invariably abdominal pain of the visceral type, resulting from appendiceal contractions or distention of the lumen. It is usually poorly localized in the periumbilical or epigastric region with an accompanying urge to defecate or pass flatus, neither of which relieves the distress. This visceral pain is mild, often cramping, and rarely catastrophic in nature, usually lasting 4 to 6 h, but it may not be noted bystoic individuals or by some patients during sleep. As inflammation spreads to the parietal peritoneal surfaces, the pain becomes somatic, steady, and more severe, aggravated by motion or cough, and usually located in the right lower quadrant. Anorexia is very common; a hungry patient does not have acute appendicitis.

Nausea and vomiting occur in 50 to 60% of cases, but vomiting is usually self-limited. The development of nausea and vomiting before the onset of pain is extremely rare. Change in bowel habit is of little diagnostic value, since any or no alteration may be observed, although the presence of diarrhea caused by an inflamed appendix in juxtaposition to the sigmoid may cause serious diagnostic difficulties. Urinary frequency and dysuria occur if the appendix lies adjacent to the bladder. The typical sequence of symptoms occurs in only 50 to 60% of patients.

Physical findings :

The diagnosis cannot be established unless tenderness can be elicited. While tenderness is sometimes absent in the early visceral stage of the disease, it ultimately always develops and is found in any location corresponding to the position of the appendix. Abdominal tenderness may be completely absent if a retrocecal or pelvic appendix is present, in which case the sole physical finding may be tenderness in the flank or on rectal or pelvic examination. Percussion, rebound tenderness, and referred rebound tenderness are often, but not invariably, present; they are most likely to be absent early in the illness. Flexion of the right hip and guarded movement by the patient are due to parietal peritoneal involvement.

Hyperesthesia of the skin of the right lower quadrant and a positive psoas or obturator sign are often late findings and are rarely of diagnostic value. When the inflamed appendix is in close proximity to the anterior parietal peritoneum, muscular rigidity is present yet is often minimal early.

The temperature is usually normal or slightly elevated [37.2 to 380 C (99 to 100.5 0F)], but a temperature _38.3 0C (101 0F) should suggest perforation. Tachycardia is commensurate with the elevation of the temperature. Rigidity and tenderness become more marked as the disease progresses to perforation and localized or diffuse peritonitis. Distention is rare unless severe diffuse peritonitis has developed. The disappearance of pain and tenderness just before perforation is extremely unusual. A mass may develop if localized perforation has occurred but will not usually be detectable before 3 days after onset.

While the typical historic sequence and physical findings are present in 50 to 60% of cases, a wide variety of atypical patterns of disease are encountered, especially at the age extremes and during pregnancy. Infants under 2 years of age have a 70 to 80% incidence of perforation and generalized peritonitis. Any infant or child with diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain is highly suspect. Fever is much more common in this age group, and abdominal distention is often the only physical finding.

DIAGNOSIS :

Physical examination in a patient with suspected appendicitis includes several special examination maneuvers:

- Rovsing sign: Tenderness of the right lower quadrant or palpation of the left lower quadrant

- Psoas sign: Increase in pain when the right leg is passively flexed while the patient is in the left lateral decubitus position

- Obturator sign: Increase in pain when the right hip is passively internally rotated while the patient is supine with a flexed right hip and knee

Investigations :

Leukocytosis (30% of patients with appendicitis had a normal WBC count with over 90% of these patients having a concomitant left shift). 24–95% of plain radiographs in patients with appendicitis are abnormal.

Diagnosis is based primarily on clinical grounds. Although moderate leukocytosis of 10,000 to 18,000 cells/_L is frequent (with a concomitant left shift), the absence of leukocytosis does not rule out acute appendicitis. Leukocytosis of _20,000 cells/_L suggests probable perforation. Anemia and blood in the stool suggest a primary diagnosis of carcinoma of the cecum, especially in elderly individuals. The urine may contain a few white or red blood cells without bacteria if the appendix lies close to the right ureter or bladder. Urine analysis is most useful in excluding genitourinary conditions that may mimic acute appendicitis.

Abnormal findings include an appendicolith, blurring of the psoas muscle margin, appendiceal gas, and free air. The CT scan is 96% sensitive in identifying appendicitis compared to ultrasound which has a 76–95% sensitivity. Findings on ultrasound may be limited by body habitus or the technician’s skill.

Ultrasonography is the investigation of choice and distended thick-walled appendix is seen. An obstructing faecolith and surrounding fluid exudate may be present. Non-filling of the appendix on barium enema is not a significant finding unless associated with an indentation along the base of the barium-filled caecum, which then suggests a chronic abscess or mucocoele of the appendix.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS :

It is probably better to err slightly in the direction of overdiagnosis, since delay is associated with perforation and increased morbidity and mortality. In unperforated appendicitis, the mortality rate is 0.1%, little more than that associated with general anesthesia; for perforated appendicitis, overall mortality is 3% (15% in the elderly). In doubtful cases, 4 to 6 h of observation is always more beneficial than harmful.

The most common conditions discovered at operation when acute appendicitis is erroneously diagnosed are, in order of frequency, mesenteric lymphadenitis, no organic disease, acute pelvic inflammatory disease, ruptured graafian follicle or corpus luteum cyst, and acute gastroenteritis. In addition, acute cholecystitis, perforated ulcer, acute pancreatitis, acute diverticulitis, strangulating intestinal obstruction, ureteral calculus, and pyelonephritis may present diagnostic difficulties.

COMPLICATIONS OF APPENDICITIS :

If appendicitis is not treated, the appendix can burst and cause potentially life-threatening infections.

Peritonitis :

If your appendix bursts, it releases pus to other parts of the body, which can cause an infection in the abdomen called peritonitis.

Peritonitis is the painful swelling of the abdomen area around the stomach and liver. The condition causes your normal bowel movements to stop and your bowel to become blocked.

This causes:

- severe abdominal pain

- a fever of 38ºC (100.4ºF) or more

- a rapid heartbeat

If peritonitis is not treated immediately it can cause long-term problems and may even be fatal.

Abscess :

Sometimes an abscess forms around a burst appendix. An abscess is a painful collection of pus that results from the body’s attempt to fight an infection.

Abscesses can be treated using antibiotics, but in some cases the pus may need to be drained from the abscess.(18)

TREATMENT:

The treatment for acute appendicitis is appendicectomy. There is a perception that urgent operation is essential to prevent the increased morbidity and mortality of peritonitis. While there should be no unnecessary delay, all patients, particularly those most at risk of serious morbidity, benefit by a short period of intensive preoperative preparation. Intravenous fluids, sufficient to establish adequate urine output (catheterisation is needed only in the very ill), and appropriate antibiotics should be given.

There is ample evidence that a single peroperative dose of antibiotics reduces the incidence of postoperative wound infection. When peritonitis is suspected, therapeutic intravenous antibiotics to cover Gram-negative bacilli as well as anaerobic cocci should be given. Hyperpyrexia in children should be treated with salicylates in addition to antibiotics and intravenous fluids. With appropriate use of intravenous fluids and parenteral antibiotics, a policy of deferring appendicectomy after midnight to the first case on the following morning does not increase morbidity. However, when acute obstructive appendicitis is recognised, operation should not be deferred longer than it takes to optimise the patient’s condition.

Pre-operative investigations in appendicitis

Routine

■ Full blood count

■ Urinalysis

Selective

■ Pregnancy test

■ Urea and electrolytes

■ Supine abdominal radiograph

■ Ultrasound of the abdomen/pelvis

■ Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen

Appendectomy

Claudius Amyand successfully removed an acutely inflamed appendix from the hernial sac of a boy in 1736. The first surgeon to perform deliberate appendicectomy for acute appendicitis was Lawson Tait in May 1880. The patient recovered; however, the case was not reported until 1890. Meanwhile, Thomas Morton was the first to diagnose appendicitis, drain the abscess and remove the appendix with recovery, publishing his findings in 1887. Appendicectomy should be performed under general anaesthetic with the patient supine on the operating table. When a laparoscopic technique is to be used, the bladder must be empty (ensure that the patient has voided before leaving the ward). Prior to preparing the entire abdomen with an appropriate antiseptic solution, the right iliac fossa should be palpated for a mass.

If a mass is felt, it may, on occasion, be preferable to adopt a conservative approach (see below). Draping of the abdomen is in accordance with the planned operative technique, taking account of any requirement to extend the incision or convert a laparoscopic technique to an open operation.

Conventional appendectomy

When the preoperative diagnosis is considered reasonably certain, the incision that is widely used for appendicectomy is the so called gridiron incision (gridiron: a frame of cross-beams to support a ship during repairs).

Criteria for stopping conservative treatment of anappendix mass

■ A rising pulse rate

■ Increasing or spreading abdominal pain

■ Increasing size of the mass

Removal of the appendix

The caecum is identified by the presence of taeniae coli and, using a finger or a swab, the caecum is withdrawn. A turgid appendix may be felt at the base of the caecum. Inflammatory adhesions must be gently broken with a finger, which is then hooked around the appendix to deliver it into the wound. The appendix is conveniently controlled using a Babcock or Lane’s forceps applied in such a way as to encircle the appendix and yet not damage it. The base of the mesoappendix is clamped in artery forceps, divided and ligated. When the mesoappendix is broad, the procedure must be repeated with a second or, rarely, a third artery forceps. The appendix, now completely freed, is crushed near its junction with the caecum in artery forceps, which is removed and reapplied just distal to the crushed portion. An absorbable 2/0 ligature is tied around the crushed portion close to the caecum. The appendix is amputated between the artery forceps and the ligature.

An absorbable 2/0 or 3/0 purse-string or ‘Z’ suture may then be inserted into the caecum about 1.25 cm from the base. The stitch should pass through the muscle coat, picking up the taeniae coli. The stump of the appendix is invaginated while the purse-string or ‘Z’ suture is tied, thus burying the appendix stump. Many surgeons believe invagination of the appendiceal stump is unnecessary.

Retrograde appendicectomy

When the appendix is retrocaecal and adherent, it is an advantage to divide the base between artery forceps. The appendiceal vessels are then ligated, the stump ligated and invaginated, and gentle traction on the caecum will enable the surgeon to deliver the body of the appendix, which is then removed from base to tip. Occasionally, this manoeuvre requires division of the lateral peritoneal attachments of the caecum.

Drainage of the peritoneal cavity

This is usually unnecessary provided adequate peritoneal toilet has been done. If, however, there is considerable purulent fluid in the retrocaecal space or the pelvis, a soft silastic drain may be inserted through a separate stab incision. The wound should be closed using absorbable sutures to oppose muscles and aponeurosis.

Laparoscopic appendicectomy

The most valuable aspect of laparoscopy in the management of suspected appendicitis is as a diagnostic tool, particularly in women of child-bearing age. The placement of operating ports may vary according to operator preference and previous abdominal scars. The operator stands to the patient’s left and faces a video monitor placed at the patient’s right foot. A moderate Trendelenburg tilt of the operating table assists delivery of loops of small bowel from the pelvis. The appendix is found in the conventional manner by identification of the caecal taeniae and is controlled using a laparoscopic tissue-holding forceps. By elevating the appendix, the mesoappendix is displayed. A dissecting forceps is used to create a window in the mesoappendix to allow the appendicular vessels to be coagulated or ligated using a clip applicator.

The appendix, free of its mesentery, can be ligated at its base with an absorbable loop ligature, divided and removed through one of the operating ports. It is not usual to invert the stump of the appendix. A single absorbable suture is used to close the linea alba at the umbilicus, and the small skin incisions may be closed with subcuticular sutures. Patients who undergo laparoscopic appendicectomy are likely to have less postoperative pain and to be discharged from hospital and return to activities of daily living sooner than those who have undergone open appendicectomy. While the incidence of postoperative wound infection is lower after the laparoscopic technique, the incidence of postoperative intra-abdominal sepsis may be higher in patients operated on for gangrenous or perforated appendicitis. There may be an advantage for laparoscopic over open appendicectomy in obese patients.

Appendicitis complicating Crohn’s disease

Occasionally, a patient undergoing surgery for acute appendicitis is found to have concomitant Crohn’s disease of the ileocaecal region. Providing that the caecal wall is healthy at the base of the appendix, appendicectomy can be performed without increasing the risk of an enterocutaneous fistula. Rarely, the appendix is involved with the Crohn’s disease. In this situation, a conservative approach may be warranted, and a trial of intravenous corticosteroids and systemic antibiotics can be used to resolve the acute inflammatory process.

Appendix abscess

Failure of resolution of an appendix mass or continued spiking pyrexia usually indicates that there is pus within the phlegmonous appendix mass. Ultrasound or abdominal CT scan may identify an area suitable for the insertion of a percutaneous drain. Should this prove unsuccessful, laparotomy though a midline incision is indicated.

Pelvic abscess

Pelvic abscess formation is an occasional complication of appendicitis and can occur irrespective of the position of the appendix within the peritoneal cavity. The most common presentation is a spiking pyrexia several days after appendicitis; indeed, the patient may already have been discharged from hospital. Pelvic pressure or discomfort associated with loose stool or tenesmus is common. Rectal examination reveals a boggy mass in the pelvis, anterior to the rectum, at the level of the peritoneal reflection. Pelvic ultrasound or CT scan will confirm. Treatment is transrectal drainage under general anaesthetic.

Management of an appendix mass

If an appendix mass is present and the condition of the patient is satisfactory, the standard treatment is the conservative Ochsner–Sherren regimen. This strategy is based on the premise that the inflammatory process is already localised and that inadvertent surgery is difficult and may be dangerous. It may be impossible to find the appendix and, occasionally, a faecal fistula may form. For these reasons, it is wise to observe a non-operative programme but to be prepared to operate should clinical deterioration occur.

Careful recording of the patient’s condition and the extent of the mass should be made and the abdomen regularly re-examined. It is helpful to mark the limits of the mass on the abdominal wall using a skin pencil. A contrast-enhanced CT examination of the abdomen should be performed and antibiotic therapy instigated. An abscess, if present, should be drained radiologically. Temperature and pulse rate should be recorded 4-hourly and a fluid balance record maintained. Clinical deterioration or evidence of peritonitis is an indication for early laparotomy.

Clinical improvement is usually evident within 24–48 hours. Failure of the mass to resolve should raise suspicion of a carcinoma or Crohn’s disease. Using this regimen, approximately 90% of cases resolve without incident. The great majority of patients will not develop recurrence, and it is no longer considered advisable to remove the appendix after an interval of 6–8 weeks.

Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications following appendicectomy are relatively uncommon and reflect the degree of peritonitis that was present at the time of operation and intercurrent diseases that may predispose to complications.

Check-list for unwell patient following appendicectomy

■ Examine the wound and abdomen for an abscess

■ Consider a pelvic abscess and perform a rectal examination

■ Examine the lungs – pneumonitis or collapse

■ Examine the legs – consider venous thrombosis

■ Also Examine the conjunctivae for an icteric tinge and the liver for enlargement, and enquire whether the patient has had rigors (pylephlebitis)

■ Examine the urine for organisms (pyelonephritis)

■ Suspect subphrenic abscess

Wound infection

Wound infection is the most common postoperative complication, occurring in 5–10% of all patients. This usually presents with pain and erythema of the wound on the fourth or fifth postoperative day, often soon after hospital discharge. Treatment is by wound drainage and antibiotics when required. The organisms responsible are usually a mixture of Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobic bacteria, predominantly Bacteroides species and anaerobic streptococci.

Intra-abdominal abscess

Intra-abdominal abscess has become a relatively rare complication after appendicectomy with the use of peroperative antibiotics. Postoperative spiking fever, malaise and anorexia developing 5–7 days after operation suggest an intraperitoneal collection. Interloop, paracolic, pelvic and subphrenic sites should be considered. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT scanning greatly facilitate diagnosis and allow percutaneous drainage. Laparotomy should be considered in patients suspected of having intra-abdominal sepsis but in whom imaging fails to show a collection, particularly those with continuing ileus.

Ileus

A period of adynamic ileus is to be expected after appendicectomy, and this may last a number of days following removal of a gangrenous appendix. Ileus persisting for more than 4 or 5 days, particularly in the presence of a fever, is indicative of continuing intra-abdominal sepsis and should prompt further investigation (see above). Rarely, early during postoperative recovery, a Richter’s type of hernia may occur at the site of a laparoscopic port insertion and may be confused with a postoperative ileus. A CT scan is usually definitive.

Respiratory

In the absence of concurrent pulmonary disease, respiratory complications are rare following appendicectomy. Adequate postoperative analgesia and physiotherapy, when appropriate, reduce the incidence.

Venous thrombosis and embolism

These conditions are rare after appendicectomy, except in the elderly and in women taking the oral contraceptive pill. Appropriate prophylactic measures should be taken in such cases.

Portal pyaemia (pylephlebitis)

This is a rare but very serious complication of gangrenous appendicitis associated with high fever, rigors and jaundice. It is caused by septicaemia in the portal venous system and leads to the development of intrahepatic abscesses (often multiple). Treatment is with systemic antibiotics and percutaneous drainage of hepatic abscesses as appropriate.

Faecal fistula

Leakage from the appendicular stump occurs rarely, but may follow if the encircling stitch has been put in too deeply or if the caecal wall was involved by oedema or inflammation. Occasionally, a fistula may result following appendicectomy in Crohn’s disease. Conservative management with low-residue enteral nutrition will usually result in closure.

Adhesive intestinal obstruction

This is the most common late complication of appendicectomy. At operation, a single band adhesion is often found to be responsible. Occasionally, chronic pain in the right iliac fossa is attributed to adhesion formation after appendicectomy. In such cases, laparoscopy is of value in confirming the presence of adhesions and allowing division.

Recurrent acute appendicitis

Appendicitis is notoriously recurrent. It is not uncommon for patients to attribute such attacks to ‘biliousness’ or dyspepsia. The attacks vary in intensity and may occur every few months, and the majority of cases ultimately culminate in severe acute appendicitis. If a careful history is taken from patients with acute appendicitis, many remember having had milder but similar attacks of pain. The appendix in these cases shows fibrosis indicative of previous inflammation. Chronic appendicitis, per se, does not exist; however, there is evidence of altered neuroimmune function in the myenteric nerves of patients with so called recurrent appendicitis (Bouchler).

DIET FOR APPENDICITIS :

For a person suffering from appendicitis, the first and most important thing to keep in mind is to avoid eating anything solid and stick to just drinking water to flush out harmful substances from the body. After the first three days, the patient should only be allowed to drink fresh fruit juices for the next few days. After 3-4 days the patient should be put on a complete fruit diet for the next 5-6 days. Once the symptoms start subsiding the patient should start following a well balanced diet that is full of fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and seeds. Water and fluid intake should also be high to avoid accumulation of toxins in the system. Foods like dairy products, meats and refined sugar products should be completely avoided while recovering from appendicitis. Simple recipes like brown rice with vegetables such as green peppers, broccoli, cauliflower, beans and peas are easy to digest and are high in fiber which is very beneficial to appendicitis patients. Other preparations like chicken soup and steamed vegetable salads are also very good for recovering patients.

REPERTORY :

REPERTORY OF THE HOMOEOPATHIC MATERIA MEDICA- J.T.KENT

Abdomen- Inflammation (Peritonitis, Enteritis, etc.), appendicitis :

Bell., Bry., cadm., calc-s., chel., chin., cocc., con., crot-c., dulc., echi., graph., hep., lach., lyc., Merc-c., merc., nit-ac., Phos., plb., Sil., ter. (p. 552)

Abdomen, pain, iliac region, right :

Cocc., kali-c., phos., phys., pic-ac., ptel., sumb. (p. 566)

Stomach, appetite, wanting :

Abrot., absin., acet-ac., acon., Act-r., æsc., æth., agar., ail., all-c., aloe., alum., am-c., am-m., ambr., anac., ant-c., ant-t., anthr., apis., arg-m., arg-n., arn.,ars-h., ars-i., Ars., arum-t., Asar., aster., aur-m., aur., bapt., bar-c., bar-i., bar-m., bell., benz., berb., bol., bor., bov., brach., bry., cact., calad., calc-ars., calc-p., calc-s., Calc., camph., canth., caps., carb-ac., carb-an., carb-s., carb-v., card-m., caust., Cham., Chel., chin-a., chin-s., Chin., chlor., cic., cina., cinnb., Cocc., coff., colch.,coloc., con., cop., cor-r., crot-t., cupr-ar., cupr., Cycl., daph., dig., dros., dulc., echi., elat., eup-per., ferr-ar., ferr-i., ferr-p., Ferr., fl-ac., gels., glon., gran., graph., guai.,gymn., hep., hydr., hydrc., hyos., hyper., ign., ind., indg., iod., ip., iris., jatr., jug-c., jug-r., kali-ar., Kali-bi., kali-br., kali-c., kali-chl., kali-i., kali-n., kali-p., kali-s.,kreos., lach., lact., laur., lec., led., lil-t., lob., Lues., Lyc., lyss., mag-c., mag-m., mag-s., manc., mang., med., meph., merc-c., merc., mez., mur-ac., murx., myric., naja., nat-a., nat-c., Nat-m., nat-p., nat-s., nicc., nit-ac., nux-m., Nux-v., olnd., op., osm., ox-ac., petr., ph-ac., Phos., phyt., pic-ac., pip-m., plat., plb., podo., psor., ptel.,Puls., raph., rat., Rhus-t., sabad., sabin., sang., sarr., Scil., sec., senec., seneg., Sep., Sil., sol-t-æ., spig., stann., stram., stront., sul-ac., Sulph., sumb., tab., tarent., tep.,ter., thu., trom., upa., urt-u., verat., vip., xan., zinc., zing. (p. 479)

Stomach, nausea :

Absin., acet-ac., acon., Act-r., act-sp., æsc., æth., agar., agn., ail., all-s., alum., alumn., am-c., am-m., ambr., anac., anan., Ant-c., Ant-t., apis., apoc., apom.,aran., arg-m., Arg-n., arn., ars-h., ars-i., Ars., arund., asaf., asar., aster., aur-m-n., aur., bapt., bar-c., bar-i., bar-m., Bell., benz-ac., berb., bism-ox., bol., bor., both., bov.,brach., brom., bry., bufo-r., cact., cadm., cahin., calc-p., calc-s., calc., camph., cann-s., canth., caps., carb-ac., carb-an., Carb-s., carb-v., card-m., carl., cast., caul., caust.,Cham., chel., chin-a., chin-s., Chin., chion., chr-ac., cina., cist., clem., Cocc., cod., coff., Colch., coll., coloc., com., con., cond., cop., cor-r., corn., crot-c., crot-h., crot-t.,cub., cupr-ar., cupr-s., Cupr., cycl., daph., Dig., dios., dros., Dulc., echi., elaps., elat., eug., eup-per., eupho., euphr., eupi., Evon., ferr-ar., ferr-i., ferr-p., ferr., fl-ac., form.,gamb., gels., gent-c., gent-l., glon., gran., graph., grat., guai., ham., Hell., Hep., hura., hydr., hydrc., hyos., hyper., ign., indg., iod., Ip., Ir-f., Iris., jatr., jug-r., Kali-ar., kali-bi., Kali-c., kali-chl., kali-i., kali-n., kali-p., kali-s., kalm., kreos., lac-c., lach., lachn., lact-ac., lact., laur., lec., led., lil-t., lith., Lob., Lues., lyc., lyss., mag-c., mag-m., mag-p.,mag-s., manc., mang., med., meny., meph., merc-c., merc-i-f., merc-i-r., merc., merl., mez., mosch., mur-ac., mygal., naja., nat-a., nat-c., Nat-m., nat-p., nat-s., nicc., nit-ac.,nux-m., Nux-v., ol-an., olnd., onos., op., ox-ac., pæon., par., Petr., ph-ac., phel., phos., phys., phyt., pic-ac., plan., plat., plb., podo., prun-s., psor., ptel., Puls., ran-b., ran-s.,raph., rat., rheum., rhod., Rhus-t., rhus-v., rumx., ruta., sabad., sabin., samb., Sang., sars., Scil., sec., sel., senec., seneg., Sep., Sil., spig., spong., stann., staph., stram., stront., stry., sul-ac., Sulph., sumb., Tab., tarax., tarent., tax., ter., ther., thu., upa., uran., ust., Valer., verat-v., Verat., vesp., vinc., viol-t., vip., wye., xan., Zinc., zing. (p. 504)

Stomach, vomiting :

Absin., acet-ac., Acon., Act-r., æsc., Æth., agar., alet., all-c., alumn., am-c., am-m., ambr., anac., Ant-c., Ant-t., anthr., Apis., apoc., Apom., aran., arg-c.,Arg-n., arn., ars-h., ars-i., Ars., arum-m., asar., asc-t., aur-m., aur., bapt., bar-c., bar-i., bar-m., bell., bism-ox., bor., both., Bry., bufo-r., cact., Cadm., cahin., calc-p., calc-s., calc., camph., cann-i., cann-s., canth., carb-ac., carb-s., caust., Cham., chel., chin-a., chin-s., Chin., chlol., cic., cina., coc-c., cocc., coff., Colch., coll., coloc., con., cop.,crot-c., crot-h., crot-t., cub., cupr-ar., cupr-s., Cupr., cycl., dig., dor., dros., dulc., elaps., eup-per., eupho., ferr-ar., ferr-i., ferr-p., Ferr., form., Gamb., gels., glon., gran.,graph., grat., hell., hep., hydr., hyos., ign., indg., iod., Ip., Iris., kali-ar., kali-bi., kali-br., kali-c., kali-i., kali-p., kali-s., kalm., Kreos., lac-d., lach., laur., Lob., lyc., mang.,merc-c., merc-d., merc., mez., mosch., mur-ac., naja., nat-m., nat-p., nit-ac., nux-m., Nux-v., olnd., op., ox-ac., pæon., petr., ph-ac., Phos., phyt., Plb., podo., psor., ptel.,Puls., rat., rhod., rhus-t., ruta., sabin., sal-ac., samb., sang., Scil., sec., sel., seneg., sep., Sil., sol-n., stry., sul-ac., Sulph., Tab., tarent., tep., ter., ther., thu., tub., uran., valer.,Verat-v., Verat., wye., zinc. (p. 531)

BOGER BOENNINGHAUSEN’S CHARACTERISTICS & REPERTORY C.M.BOGER

[ABDOMEN] Ileo-caecal region: (14)

ARS. BAPT. BELL. BRY. COLOC. Ferr-p. mag-c. Merc. Nux-v. OP. RHUS-T. sep. SUL-I. SULPH. (p. 545)

[NAUSEA AND VOMITING] Nausea: (145)

Acon. adon. Agar. Agn. all-c. ALUM. Am-c. am-m. ambr. Anac. Ang. ANT-C. ANT-T. apis ARG-MET. arg-n. ARN. ARS. asaf. ASAR. aur. BAR-C. bar-m. BELL. Bism. Borx. Bov. brom. BRY. calad. calc. CAMPH. Canth. caps. CARB-AN. CARB-V. CAUST. Cham. chel. CHIN. chinin-s. Cic. cina clem. Cocc. Coff. Colch. coloc. Con. Croc. crot-h. crot-t. Cupr. Cycl. DIG. Dros. DULC. euph. euphr. ferr. glon. GRAPH. grat. guaj. Hell. HEP. hydr. hyos. IGN. IOD. IP. iris Kali-bi. kali-br. KALI-C. kali-n. KREOS. LACH. Laur. led. lept. Lob. LYC. Mag-c. MAG-M. mang. meny. MERC. Mez. Mosch. mur-ac. naja NAT-C. NAT-M. NIT-AC. nux-m. NUX-V. ol-an. Olnd. op. pall. PETR. PH-AC. PHOS. Plat. Plb. Prun. PULS. Ran-b. Ran-s. rheum rhod. RHUS-T. RUTA Sabad. sabin. samb. Sang. SARS. SEC. sel. seneg. SEP. SIL. Spig. spong. SQUIL. STANN. STAPH. stram. stront-c. Sul-ac. SULPH. Tab. tarax. teucr. ther. thuj. Valer. VERAT. Verat-v. verb. viol-t. vip. zinc. (p. 500)

[NAUSEA AND VOMITING – Vomiting] – in general: (96)

Acon. am-c. am-m. AMBR. anac. Ant-c. ANT-T. apis arg-n. ARN. ARS. Asar. bar-c. BELL. bism. borx. Bov. BRY. Calc. camph. Canth. caps. CARB-V. CAUST. CHAM. CHIN. CIC. CINA cocc. coff. Colch. COLOC. Con. CUPR. Dig. DROS. Dulc. euph. FERR. Graph. grat. GUAJ. hell. Hep. Hyos. IGN. iod. IP. Kali-bi. kali-c. kali-n. KREOS. LACH. laur. led. LYC. mag-c. MERC. merc-c. mez. nat-c. NAT-M. nit-ac. Nux-m. NUX-V. Olnd. Op. PETR. ph-ac. PHOS. phyt. PLB. podo. PULS. rhod. rhus-t. sabad. sabin. samb. SEC. seneg. SEP. SIL. spig. squil. STANN. Stram. Stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. TAB. ther. thuj. valer. VERAT. zinc. (p. 502)

[FEVER – Pathological types] – inflammatory: (55)

ACON. APIS arn. ARS. bar-c. BELL. BRY. calad. Calc. Camph. CANTH. caust. CHAM. Chin. cocc. Coff. colch. coloc. con. dig. dros. dulc. Hep. HYOS. ign. Ip. Kali-c. KALI-N. Lach. laur. LYC. MERC. Mez. nat-c. nat-m. Nit-ac. NUX-V. Op. ph-ac. PHOS. PULS. Rhus-t. sabad. sec. seneg. Sep. SIL. Spig. spong. Squil. Staph. stram. sul-ac. Sulph. Verat. (p. 1003)

BOENNINGHAUSEN’S THERAPEUTIC POCKET BOOK T.F.ALLEN

[Parts of the body and organs – Abdomen; internal] – Umbilicus: (95)

ACON. Alum. am-c. AM-M. ambr. ANAC. ant-c. ant-t. Arn. Asaf. bar-c. BELL. BOV. BRY. calad. Calc. camph. cann-s. canth. Caps. Carb-an. Carb-v. Caust. Cham. CHEL. CHIN. CINA Cocc. colch. Coloc. Con. Dig. DULC. Graph. guaj. Hell. hep. Hyos. IGN. iod. IP. kali-c. Kali-n. KREOS. lach. Laur. m-ambo. m-arct. m-aust. Mag-c. Mag-m. Mang. meny. merc. Mez. MOSCH. Mur-ac. NAT-C. NUX-M. NUX-V. OLND. op. par. PH-AC. Phos. PLAT. PLB. Puls. Ran-b. Ran-s. RHEUM rhod. RHUS-T. ruta sabin. Sars. seneg. SEP. Sil. SPIG. spong. Stann. Staph. stram. STRONT-C. SUL-AC. SULPH. tarax. teucr. thuj. Valer. VERAT. VERB. viol-t. Zinc. (p. 80)

[Parts of the body and organs – Nausea – nausea] . Abdomen; in: (25)

Agn. Ant-t. Bell. BRY. cic. cocc. croc. Cupr. Cycl. hell. hep. ip. m-arct. Mang. nux-m. par. PULS. Rheum ruta Samb. sil. stann. staph. teucr. valer. (p. 74)

[Parts of the body and organs – Nausea – vomiting] . general; in: (85)

Acon. am-c. am-m. anac. ANT-C. Ant-t. arg-met. Arn. ARS. Asar. bar-c. BELL. bism. Borx. bov. BRY. CALC. camph. Cann-s. Canth. caps. carb-v. caust. CHAM. CHIN. cic. CINA cocc. coff. Colch. coloc. Con. CUPR. Dig. DROS. Dulc. euph. FERR. Graph. hell. Hep. HYOS. IGN. iod. IP. kali-c. kali-n. Kreos. lach. laur. led. Lyc. mag-c. Merc. mez. nat-c. nat-m. nit-ac. nux-m. NUX-V. Olnd. Op. petr. ph-ac. PHOS. PLB. PULS. rhod. rhus-t. sabad. sabin. samb. SEC. seneg. SEP. SIL. squil. Stann. Stram. sul-ac. SULPH. thuj. valer. VERAT. zinc. (p. 75)

[Fever – Heat] – general; in: (121)

ACON. agar. agn. alum. am-c. am-m. ambr. Anac. ang. ant-c. ant-t. arg-met. ARN. ARS. asaf. asar. bar-c. BELL. bism. borx. bov. BRY. calad. CALC. camph. cann-s. canth. caps. carb-an. Carb-v. Caust. CHAM. chel. Chin. cic. cina clem. cocc. Coff. colch. coloc. Con. croc. cupr. cycl. dig. dros. Dulc. euph. ferr. Graph. guaj. hell. HEP. Hyos. IGN. iod. Ip. Kali-c. kali-n. kreos. lach. laur. led. Lyc. m-ambo. M-arct. m-aust. Mag-c. Mag-m. mang. meny. MERC. mez. mosch. mur-ac. nat-c. nat-m. NIT-AC. nux-m. NUX-V. olnd. Op. par. PETR. PH-AC. PHOS. plat. plb. PULS. ran-b. Ran-s. rheum rhod. RHUS-T. ruta Sabad. sabin. Samb. sars. sec. sel. seneg. Sep. SIL. Spig. Spong. Squil. Stann. Staph. Stram. stront-c. sul-ac. SULPH. tarax. teucr. Thuj. valer. verat. Viol-t. zinc. (p. 256)

APPENDICITIS – DIFFERENTIATION OF REMEDIES :

The selection of remedy is based upon the theory of individualization and symptoms similarity by using holistic approach. This is the only way through which a state of complete health can be regained by removing all the sign and symptoms from which the patient is suffering. The aim of homeopathy is not only to treat appendicitis symptoms but to address its underlying cause and individual susceptibility. As far as therapeutic medication is concerned, several medicines are available for appendicitis symptoms treatment that can be selected on the basis of cause, sensation, modalities of the complaints.

The goals of therapy are to eradicate the infection and prevent complications.

Homeopathic medicines commonly used in the case of appendicitis are Ars Alb, Belladonna, Bryonia, Colocynth, Dioscorea, Echinacea, Ferrum phos, Hepa sulp, Ignatia, Iris Tenax, Kali bich, Lachesis, Lillium Tig, Lycopodium, Mag phos, Nat sulp, Nux vom, Plumbum, Pulsatilla, Pyrogen, Rhus tox, Sulphur, etc. These Medicines should be taken under the advice and diagnosis of a qualified Homeopath.

Homeopathy is indicated in the first day or the second day, in the early stage. Homoeopathy may help some cases. However, acute appendicitis may turn out to be a surgical condition, where homeopathy may not work. Acute appendicitis can be best managed under proper supervision of a surgeon. Homeopathy is indicated for the treatment of chronic and recurrent appendicitis. The medicines help for complete recovery and strengthen the immunity. Every case of appendicitis needs professional evaluation by an experienced homeopathic physician before deciding if it is suitable for surgery or homeopathy.

ARSENICUM ALBUM :

When the condition points to sepsis Arsenicum may be the remedy. There are chills, hectic symptoms, diarrhea and restlessness, and sudden sinking of strength. It relieves vomiting in these conditions more quickly than any other remedy. Dr.Mitchell finds it more often indicated in appendicitis than Mercurius corrosives, which may also be a useful remedy. Arnica is a remady suiting septic cases and it should be employed after operations.(8)

Nausea. Vomiting violent and incessant, excited by any substance taken into the stomach. Even water is immediately thrown off the stomach. Vomiting every time after drinking. The vomit brings no relief. Frequent vomiting with apprehensions of death.(9)

COLOCYNTHIS :

Undoubtedly many cases of simple colic are diagnosed as appendicitis and operated upon. Therefore, purely colic remedies as Colocynth and Magnesia phosphoric should be studied. The foregoing remedies will be found the most commonly indicated and may be used in both operable and non-operable cases as well as in conjunction with the meritorious oil treatment of the disease.(8)s

DIOSCOREA :

Dioscorea is a good remedy for wind Colic. The Pain begins right at the umbilicus, and then radiates all over the abdomen, and even to extremities (Plumbum, with walls retracted), and, unlike Colocynth, the pain is aggravated by bending forward and relieved by straightening the body out.

FERRUM PHOS :

It has proved itself clinically in inflammation about the ileo-caecal region and their indications rest on clinical grounds only.

All febrile disturbances and inflammations at their onset, before exudation commences. In many inflammatory and some eruptive fevers, it seems to stand between the intensity of Acon. and Bell., and the dullness of Gels.

HEPAR SULPH :

Chilliness, hypersensitiveness, splinter-like pains, craving for sour and strong things are very characteristic. Feeling as if wind were blowing on some part. The side of the body on which he lies at night becomes gradually insufferably painful; he must turn.

Sensitive to pain. They let you know that they are in pain and won’t let the spot be touched. Very effective alternative to antibiotics when there is pus formation with infection. Hepar‘s pains are stitching and splinter-like where ever they occur.

Aversion to fat food. Frequent eructations, without taste or smell. Distention of stomach, compelling one to loosen the clothing. Burning in stomach. Heaviness and pressure in stomach after a slight meal.

IGNATIA :

It is the remedy for the nervous symptoms of the disease, and to be used in cases where operation has been performed and no relierf has resulted; also in those who become exceeding nervous from any abdominal pain.

KALI BICH :

Affections of the mucous membranes – eyes, nose, mouth, throat, bronchi, gastro-intestinal and genito-urinary tracts. Pains: in small spots, can be covered with point of finger (Ign.); shift rapidly from one part to another (Kali s., Lac c., Puls.); appear and disappear suddenly (Bell., Ign., Mag. p.). Gastric complaints: bad effects of beer; loss of appetite; weight in pit of stomach; flatulence; < soon after eating; vomiting of ropy mucus and blood; round ulcer of stomach (Gym.).

LACHESIS :

Pain and swolling in the region of caecum. Pain extends from right lumbar region, through inguinal region and fore part of thigh. Patient weak. This is also a valuable remedy; its great characteristics of sensitiveness all over the abdomen, and stitching from the seat of the inflammation backwards and downward to the thighs, will indicate it in this disease. The patient lies on the back with knees drawn up, and other general Lachesis symptoms present.

CLARKE – Clinical – Appendicitis. Acute pain in liver extending towards stomach,” though contrary to the general “left to right” direction, is characteristic, as I can testify.

Lach. is also one of the most prominent remedies in appendicitis.

LILIUM TIG :

Stomach.–Flatulent; nausea, with sensation of lump in stomach. Hungry; longs for meat. Thirsty, drinks often and much, and before severe symptoms.

Abdomen.–Abdomen sore, distended; trembling sensation in abdomen. Pressure downwards and backwards against rectum and anus; worse, standing; better, walking in open air. Bearing down in lower part of abdomen.

Urinary.–Frequent urging. Urine milky, scanty, hot.

Stool.–Constant desire to defecate, from pressure in rectum, worse standing. Pressure down the anus. Early-morning urgent stool. Dysentery; mucus and blood, with tenesmus, especially in plethoric and nervous women at change of life.

LYCOPODIUM :

In nearly all cases where Lycopodium is the remedy, some evidence of urinary or digestive disturbance will be found. Symptoms characteristically run from right to left, acts especially on right side of body, and are worse from about 4 to 8 pm. Intolerant of cold drinks; craves everything warm. Deep-seated, progressive, chronic diseases. Emaciation. Debility in morning. Marked regulating influence upon the glandular (sebaceous) secretions. Lycop patient is thin, withered, full of gas and dry. Lacks vital heat; has poor circulation, cold extremities. Pains come and go suddenly. Sensitive to noise and odors.

Abdomen.–Immediately after a light meal, abdomen is bloated, full. Constant sense of fermentation in abdomen, like yeast working; upper left side. Pain shooting across lower abdomen from right to left.

MAGNESIUM PHOSPHORICUM :

Pains: sharp, cutting, stabbing; shooting, stitching; lightning-like in coming and going (Bell.); intermittent, paroxysym becoming almost unberable, driving patient to frenzy; rapidly changing place (Lac c., Puls.), with a constricting sensation (Cac., Iod., Sulph.); cramping, in neuralgic affections of stomach, abdomen and pelvis (Caul., Col.). Languid, tired, exhausted; unable to sit up.

NUX VOMICA :

Stomach.–Sour taste, and nausea in the morning, after eating. Weight and pain in stomach; worse, eating, some time after. Flatulence and pyrosis. Sour, bitter eructations. Nausea and vomiting, with much retching. Ravenous hunger, especially about a day before an attack of dyspepsia. Region of stomach very sensitive to pressure (Bry; Ars). Epigastrium bloated, with pressure s of a stone, several hours after eating. Desire for stimulants. Loves fats and tolerates them well (Puls opposite). Dyspepsia from drinking strong coffee. Difficult belching of gas. Wants to vomit, but cannot.

Abdomen.–Bruised soreness of abdominal walls (Apis; Sulph). Flatulent distension, with spasmodic colic. Colic from uncovering. Liver engorged, with stitches and soreness. Colic, with upward pressure, causing short breath, and desire for stool. Weakness of abdominal ring region. Strangulated hernia (Op). Forcing in lower abdomen towards genitals. Umbilical hernia of infants.

Stool.–Constipation, with frequent ineffectual urging, incomplete and unsatisfactory; feeling as if part remained unexpelled. Constriction of rectum. Irregular, peristaltic action; hence frequent ineffectual desire, or passing but small quantities at each attempt. Absence of all desire for defecation is a contra-indication. Alternate constipation and diarrhœa. Urging to stool felt throughout abdomen. Ineffectual urging to stool; very painful; after drastic drugs. Diarrhœa after a debauch; worse, morning. Frequent small evacuations. Scanty stool, with much urging. Dysentery; stools relieve pains for a time. Constant uneasiness in rectum.

PLUMBUM :

The father-in-law of Dr. T. L. Brown, over seventy years of age, was attacked with a severe pain in the abdomen. Finally, a large, hard swelling developed in the ileo-cæcal region very sensitive to contact or to the least motion. It began to assume a bluish color, and on account of his age and extreme weakness it was thought that he must die. His daughter, however, studied up the case, and found in Raue’s Pathology the indications for Plumbum as given in therapeutic hints for typhlitis. It was administered in the 200th potency, which was followed by relief and perfect recovery.

PULSATILLA :

Symptoms ever changing: no two chills, no two stools, no two attacks alike; very well one hour, very miserable the next; apparently contradictory (Ign.).

Pains: drawing, tearing, erratic, rapidly shifting from one part to another (Kali bi., Lac c., Mang. a.); are accompanied with constant chilliness; the more severe the pain, the more severe the chill; appear suddenly, leave gradually, or tension much increases until very acute and then “lets up with a snap;” on first motion (Rhus).

Stomach.–Averse to fat food, warm food, and drink. Eructations; taste of food remains a long time; after ices, fruits, pasty. Bitter taste, diminished taste of all food. Pain as from subcutaneous ulceration. Flatulence. Dislikes butter (Sang). Heartburn. Dyspepsia, with great tightness after a meal; must loosen clothing. Thirstlessness, with nearly all complaints. Vomiting of food eaten long before. Pain in stomach an hour after eating (Nux). Weight as from a stone, especially in morning on awakening. Gnawing, hungry feeling (Abies c). Perceptible pulsation in pit of stomach (Asaf). All-gone sensation, especially in tea drinkers. Waterbrash, with foul taste in the morning.

Abdomen.–Painful, distended; loud rumbling. Pressure as from a stone. Colic, with chilliness in evening.

PYROGEN :

Pyrogen is the great remedy for septic states, with intense restlessness. “In septic fevers, especially puerperal, Pyrogen has demonstrated its great value as a homeopathic dynamic antiseptic. ” (H. C. Allen). Chronic complaints that date back to septic conditions.

Stomach.–Coffee-grounds vomiting. Vomits water, when it becomes warm in stomach.

Stool.–Diarrhœa; horribly offensive, brown-black, painless, involuntary. Constipation, with complete inertia (Opium); obstinate from impaction. Stools large, black, carrion-like, or small black balls.

Fever.–Coldness and chilliness. Septic fevers. Latent pyogenic condition. Chill begins in back. Temperature rises rapidly. Great heat with profuse hot sweat, but sweating does not cause a fall in temperature.

RHUS TOXICODENDRON :

This remedy, with its great correspondence to septic troubles, may be required, and may be indicated by its peculiar symptoms; locally, too, it has extensive swelling over the ileo-caecal region and great pain, causing an incessant restlessness. Dr.Cartier, of Paris, recommends Rhus radicans 6, in appendicitis of influenza origin at the onset.

BELLADONNA :

Medicine acute intest. conditions, colic – Abdominal pains, violent; come and disappear suddenly. Are squeezing; clawing; as if griped by nails; violent pinchings. “Violent colic, intense cramping pain, face red as fire.” Tenderness of abdomen, worst least jar. Frequent urging to stool, little or no result (Nux). Spasmodic contraction of sphincter ani. Great pain in ileo-caecal region: cannot bear slightest touch, even of bedclothes (early appendicitis. Local external applications to abort). Typical Bell. has red, hot face; big pupils: is sensitive to pressure draughts, jar.

Special remedies of appendix and caecum – Years ago, when making diagrams to show the action of remedies on parts of the body, one grasped the fact that two drugs seemed to share the honours in this area- Belladonna and Mercurius corrosivus. And one knows that Bell. has earned a great reputation for early, simple inflammation of appendix. Among its symtoms are : Great pain in right ileo-caecal region. Cannot bear the slightest touch, not even of bed covers. Tenderness aggravated by least jar.( KENT says, “The jar of the bed will often reveal to you the remedy”). Bell. has much swelling. Its inflammations throb : feel bursting. Kent also says, “There are instances where Bell. :is the remedy of all remedies in appendicitis”.

There are instances where Bell. is the remedy in appendicitis.Belladonna has dysenteric troubles.

Pain in the region of the caecum.

MERCURIUS CORROSIVES :

Medicine acute intest. conditions, colic. -Peculiar bruised sensation about caecum and along transverse colon. Tender to pressure. Appendicitis. ( Bell). Painful bloody discharges (from rectum) with vomiting. Tenesmus, persistent, incessant, with insupportable cutting, colicky pains. Diarrhoea dysentery with terrible straining before, with, and after stool. Merc. cor. is almost specific for dysentery. Very distressing tenesmus, getting worse and worse: nothing blood.

Remedies of appendix and caecum – Kent has this drug down in black type for appendicitis. Merc. corr. is violent and active. Has far more activity, excitement and burning. Caecal region and transverse colon painful. Bloated abdomen. Characteristic : Great tenesmus of rectum, the “never-get-done” remedy. Abdomen bruised, bloated, tender to least touch. Tenesmus of bladder, also. Hot urine passed drop by drop.

BRYONIA ALBA :

Special remedies of appendix and caecum – Appendicitis : peritonitis. Must keep very still; stools hard, dry, as if burnt. Pain in a limited spot : dull, throbbing or sticking. Bry. is better lying on painful side, for pressure and to limit movement. Lies knees drawn up. Better for heat to inflamed part.

Sensitive abdomen; appendicitis. Constipation; hard, dry stool.

ECHINACEA PURPUREA :

Special remedies of appendix and caecum – (In Repertory for Appendicitis). Boericke says : “It acts on appendix and has been used for appendicitis. But remember, it promotes suppuration, and a neglected appendix with pus formation would probably rupture sooner under its use”. -Another condition to which Natrum sulph. patients are prone is a fairly acute attack of appendicitis, with extreme pains in the cecal region.

Lymphatic inflammation; crushing injuries. Compare : Iris florentina-Orris-root-(delirium, convulsions, and paralysis); Iris factissima (headache and hernia); Iris germanica-Blue Garden Iris-(dropsy and freckles); Iris tenax -1.minor-(dry mouth; deathly sensation at point of stomach, pain in ileo-caecal region; appendicitis. Pain from adhesions after).

Echinacea angustifolia – Clinical – Appendicitis.

Echinacea is claimed, has acted brilliantly in septic appendicitis; the tincture, 1x and 3x are the strengths used. No indications except septic condition; tiredness is characteristic.

NATRIUM SULPHURICUM :

Digestive drugs – Apparently, it is a retro-cecal appendix, because they always complain of extreme pain going right round to the back, rather than of pain ore McBurney”s Point. It is the type of appendix which is associated with a degree of jaundice. Some of the most striking results from Natrum sulph. have been in cases of appendix abscesses, where there has been a retro-cecal appendix and a tendency for the inflammation to track up and conditions suggesting a sub-phrenic. There is one other rather interesting point about this remedy, and it has no connection with the digestive system. Natrum sulph. is sometimes very well indicated in acute his joints, particularly when it is the right hip which is affected. The pain is very similar in character to that experienced in cases of appendicitis, and if there are any Natrum sulph. indications, it is worthwhile to consider its use. Two cases in hospital cleared up remarkably well on Natrum sulph., and it is apt to be forgotten for this condition.

Natrium sulphuricum – It has cured many cases resembling the first stage of appendicitis. Pain and tenderness in the whole abdomen. Flatulence; colic; rending, tearing, cutting pains throughout the abdomen; stitching pains in the abdomen; violent neuralgic pains in the abdomen; inflammation of the bowels, of the peritoneum; appendicitis.

ARNICA MONTANA :

Do not forget the symptoms of Arnica in appendicitis if you know Bryonia, Rhus tox., Belladonna, Arnica and similar remedies. The homoeopathic remedy will cure these cases, and, if you know it, you need never run after the surgeon in appendicitis except in recurrent attacks.

If you do not know your remedies, you will succumb to the prevailing notion that it is necessary to open the abdomen and remove the appendix. “Great pain in the ileo-caecal region; cannot bear the slightest touch, even the bed clothes.”

PHOSPHORUS :

Yellow, brown spots on the abdomen; petechiae over the abdomen during typhoid fever. Pale face in pleura/peritoneum-disease, red face in articular affections.

Characteristics – Although he deemed it useless he was persuaded to operate, and found a large abscess behind the colon, freely communicating with the peritoneal cavity.